Technique Over Content

Or becoming lost in the minutia at the expense of something more.

Ben and I recently bought a second-hand 12″ jointer from a woman locally with a shop in the hills of western Sonoma County. We arrived and were ushered into a structure off the main residence to behold a shop carefully housed with a surprising number of tools–top brands in sparkling condition occupying an uncommonly large proportion of the available floor space. After some introductions and a few specifications regarding the jointer–which appeared to have had limited use–we visited for a while and learned that she had managed to get a job at the local WoodCraft, where she set about satisfying a passion for tools, while making use of a 40% employee discount as if stocking a trout farm. At some juncture it dawned on us that what was missing was any evidence of a project in-progress. In fact, on closer inspection, there was no open floor space to even accommodate such a project.

We loaded up and said our goodbyes and promised to stay in touch and on the ride back, it was mentioned how there appeared not to have been any sawdust, anywhere; the floors were not only immaculate, but an expensive hardwood featuring a sub-floor radiant heat. The more we thought about it, the more sense it made: She was a tool aficionado. Her interests and passions were not in actually building anything, but in simply owning the tools and maintaining the tools and laying out a shop something closer to a postcard than a working environment. It was not a functional shop. Not a shop that had the look of being used. Not a shop that paid the mortgage or a shop that was subservient to a working woodworker’s needs, but a shop that, at best, would be relegated to the repeated practice of technique.

We mention this, here, because it is a good example of allowing the thrill and absorption of technique to overshadow the very purpose of those tools. To create products made of wood. What we remembered was a comment that she occasionally does a project. Very small projects, which reduce the error and dalliance from perfection. Tools in themselves can be an act of perfection: maintaining them and tuning them and truing them to, well . . . perfection. But the moment they become a means to an end, as in functioning workhorses, then the parables of art raise their ugly heads. No work of art is perfect. And to some–those absorbed in the compulsion of technique–the idea of anything less than perfect is intolerable.

It is a phenomenon seen elsewhere. A current customer who arrived 11 months ago with an idea for a gate situated halfway down the long stairs leading to his house. An architect, he sent a rough sketch of what he had in mind. A doable design. A price was fixed and following a week of silence, he followed up with suggestions of stained glass. The revisions were smoothed out and another price and following a week’s silence, another note with further explanations and an attached photo showing where the gate would reside. This went on and on and eventually the realization that his notes were written on Saturdays, and each of them drawn to some insignificant detail already discussed thoroughly and in essence, we were by now working in circles. But at some juncture, several months later, an advance was paid and drawings were posted and we continued our weekly discussions, dismantling and second-guessing and as time passed, his notes were more succinct and less relevant and we understood by now, about six months later, that he was paralyzed by a fear of graduating from the stage of design to the stage of building–of implementing that design. As long as he devoted a few minutes or so each Saturday to this venture, to the collaboration of the design phase of this venture, he was safe and the project remained an active part of his weekly existence. It is now, as we write, almost a year since the drawings were posted. The notes are less frequent. Once a month, making less and less sense, and often with the drawing attached with his accompanying remarks and suggestions so meticulously called out. Stuck in a place between idea and implementation seemingly forever. Unable to grasp the confidence to simply act. To move forward.

Our own approach would be the opposite, and something of a fright to both our woman with her fascination for tools and our gentleman caught up in the inertia of nothingness. More or less all of the 600+_ products on this web site were built initially as prototypes, as well as all those products through the 1970’s and 1980’s when the line was strictly one-off home furnishings. An approach that is initiated by an idea that forms in one’s head until you begin cutting wood. By that time the pace is steady and unrelenting, working from specifications that exist nowhere but the recesses of one’s own mind. There are no drawings or endless deliberations, leaving only a forgivable arena for signatory embellishments or structural revisions to the basic idea. This is not an approach that fusses over technique. It is an approach that produces at a pace the mind imagines. The techniques themselves were learned long long ago. Providing a means to an end. A well-engineered roadbed, without which your new state-of-the-art roadster would be relegated to the depressions and holidays of a dirt road.

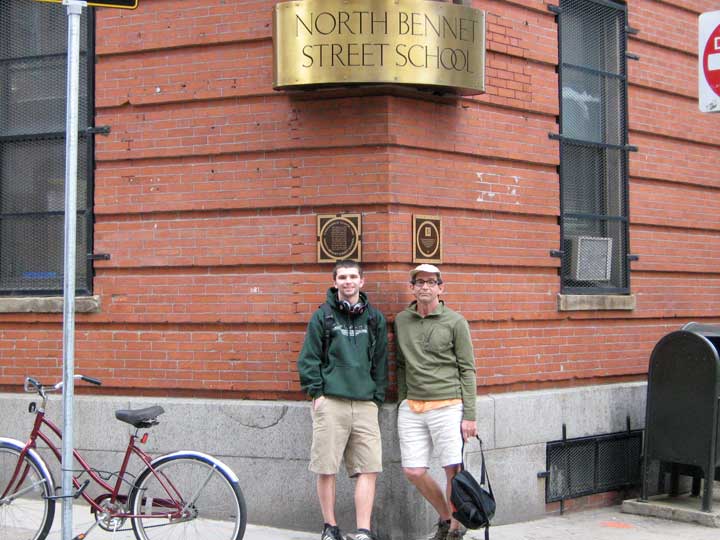

Back east, at Ben’s former school North Bennett Street in Boston, his instructors might spend six months replicating a 17th century highboy, down to the most intimate details. Hand-cut dovetails and hand-planed profiles as an approach to woodworking that is all about technique. An admirable endeavor and a perfect environment to learn technique, but one that is entirely drawn from technique. The problematic mess of design is supplanted with a piece that has been around for hundreds of years, freeing the mind to concentrate solely on the perfection of technique. Approaching such a work without detailed specifications would be unthinkable.

2010–Charles visiting Ben at North Bennett St, Boston

2010–Charles visiting Ben at North Bennett St, Boston

Technique is a learned value drawn from a known world. One can practice it and perfect it and hone it to precision, and beyond. It is doable. Content, however, offers no such guarantees. Content is spirit, or soul, reaching out for the ephemeral thought, or idea; The more tentative your reach, the less likely you’ll succeed.

Our minds are not computers. And my own mind is geared more toward a single focus than the multi-tasking of bobbing several mediums at once. The backhouse work can take time, for certain–however long it takes to reach the level of workmanship that compliments the level of excellence to which we aspire–and while slogging through this stage, enlightened simply by the ethics and discipline of work itself, the ensuing features and rough design continues to form as little more than a daydream. A form of multi-tasking, I suppose–the curating process of the overall design working subliminally while slogging through the basic mill work and primary joinery that provide the structural parameters of what’s to come. Whereas working from drawings, the known entity of, say, a 14th century highboy, removes that subliminal discretion entirely, leaving nothing to the imagination and freeing one’s focus to the entirety of reproducing the techniques employed so many centuries ago.

But few of us have the dedicated luxury of single-tasking. The Zen-ness of woodworking is a lovely thought, but in truth it is a state of mind forever jumbled with the necessities, or minutia, of any business. There is an administrative need, demanding a comprehension of finances and taxes; of negotiating accounts with shippers and lumber mills and various suppliers; of navigating the ever-changing strictures of html coding, of networked databases, of filing and the hierarchy of locating what has been filed; of marketing; of graphics and the advanced skills of Photoshop to create a graphical interface that comes to define the product as much as the product itself; of creating and maintaining a presence on the various platforms of social media; of learning the language and its correct usage toward a developed and recognizable voice and the ability to command the language to best express the thoughts in your head; of receiving and responding to the inquiries with an ability to quickly understand and comprehend the individual distinctions of each and every inquiry and comprise a solution that results in a design that results in an estimated cost in a process that can be accomplished often within 15 minutes or take weeks, sometimes months; of the need to communicate over the phone, listening and listening and forever gearing the overly cautious and overly careful toward the center; of balancing a business like any business through the surges and recessions that are, over the decades, an inevitable truth and scheduling to those fluctuating trends; of learning to balance your days with the conscious interruptions that might be likened to the vermiculite that aerates soil–i.e. aerating that medley of the above list with an afternoon swim or nap or a few pages of a novel over coffee simply to reorient your perspective. And somewhere within all the above a Zen state exists, when the foremost attention is brought to designing and cutting a self-locking haunch joint while fully aware of the more recessed thoughts of the work in its entirety, as a whole, and throughout the little prompts and cues that help make that transition–the familiar aria from a familiar opera performed by a soprano you’ve listened to for decades, a soprano who’s been dead for decades. Learning to balance the vermiculite with the soil.

To assume life can be only those moments when the coloratura, the soprano, reaches those high registers is not just unreasonable, but ridiculous. To arrive, to fully encompass those moments requires not only the sweat equity of the above paragraph but the absolute necessity of performing each of those tasks, those techniques, with an eye toward excellence. i.e. you cannot ignore technique and jump-start straight to the heart of the heart of nirvana. You cannot adopt as your guiding template or mentor someone with the approach of a Jackson Pollack, who eschewed technique and the painstaking laborious process of grasping the fundamentals for the instant expression of splattering dollops of paint on a canvas the size of a barn. There may be expressive intent somewhere in the methodology of how he flicks his wrist wielding a 6″ brush sold at the drugstore, but the result will seldom warrant the scrutiny of succeeding generations. There is no evidence that Mr. Pollock ever mastered the basics of realism, of sketching figures and forms. There is a tremendous amount of evidence, however, that he possessed a quality to promote himself and his work as one. You cannot contemplate a Pollack painting without the full and intermediating influence of the man himself anymore than you can assess that portrait of Marilyn Monroe or the can of Campbell Soup without infusing the essence of Andy Warhol.

Could Picasso paint realism? Had he developed the techniques of the genre, and mastered those techniques? There are numerous examples from the 1890’s (Self-Portrait 1896; Male Torso 1893; and First Communion 1896, among so many others that should sufficiently answer that question. The more interesting considerations are why did he choose the other paths he did? What was he exploring? What did he find? What part of him felt it necessary to move beyond his works of the late 19th century and into realms wholly unknown? Perhaps his own explanation of that process is worth mulling over.

“When I was a child, my mother said to me, ‘If you become a soldier, you’ll be a general. If you become a monk you’ll end up as the Pope.’ Instead, I became a painter and wound up as Picasso.” Pablo Picasso

A little known anecdote, corroborated from a number of sources and written accounts informs us Mr. Warhol’s compulsion for fame, and how the impatience for that fame eliminated the apprenticeship of known technique. Every morning for an hour or two he arrived to sit on the curb outside Truman Capote’s Brooklyn apartment in the slim hope of meeting the iconic self-promoter himself. He was not interested in Mr. Capote’s work– perhaps the most dexterous lyricist of his generation–but moreover it was Truman’s knack for insuring the public took notice of those gifts. His knack for educating his future audience with a splay of wizardry and hocus pocus and a self-presentation that, as the years passed, graduated into a form of performance art until ultimately the performance clipped the work itself. The world was infatuated with the artist, with Capote, and Warhol, and Pollock, and notice of the work itself–the writings, the lithographs, the paintings–rose at a pace commensurate with the artist’s global presence.

Does this suggest that someday, when the world is inhabited by all new people, and no one exists who existed when those big personalities resonated in our culture, subsequent generations will not view such work with the same overriding influence of the personality artist? Possibly. The lasting power of art can be fickle and our historical purview is often repainted in a less favorable opinion. In some sense it becomes a battle between the artist and their work, which of the two wins the attention and fascination of future generations, and does that victor stand alone without the other half? Can they study and appreciate, a century from now, the paintings of Salvador Dali if the life itself has faded from history? Will they scrutinize the work alone, with only the faintest awareness of the flamboyant life behind it. And will they wonder, stripped of it’s showmanship, what all the fuss was about? A work that hopscotches with an elitist’s premonition over the fundamentals that invite repeated scrutiny. The sort of scrutiny we bring to Picasso, tracing his roots from the earliest forms through the many transformations as proof, as evidence that he understood technique.

We are told to read James Joyce’s Ulysses as a classic on the list of any well-read literati, while few mention that this book holds its place on this list because of its impact on the known literature of the day. The stream of conscientious and inner monologue before such an approach was splattered over a roll of shelf paper fed into a typewriter with the result of Kerouac’s On The Road. Or the shocking inroads of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1928 if compared to half the titles available on any given day at Barnes and Noble. Steamy scenes are relevant. Few of the ground-breaking titles possess the narrative qualities that hold up to future readers and we must read them more with an eye to their novelty when they were originally published than to their readability from one generation to another. Kerouac embodied an adventurous freedom in his little book and presented such adventure to a generation in the 1950’s who had survived the uncertainties of war with an obsessive need to live predictable lives. On the Road preached anything but being predictable, and the suburbs were suddenly swelling with a latent need for fun when their fun years had been lived with the deprivations of a Great Depression and a war, of the solidarity and patriotism called upon to fight Germans. They dreamed, however briefly, of having sex in the backseat of a ’52 Ford careening down Route 66. They did not read Kerouac for his literary excellence. They read him for the social timeliness of his story. A story written without pause or paragraphs or even single sheets of paper, but on a continuous roll of shelving paper fed into his typewriter that was for six years soundly rejected by every publisher who saw it. After six years of painstaking rewrites, it made it’s way into print, and promptly fostered an early reaction from the reigning stylist Capote to quip that what Kerouac did was ‘talk into the typewriter. A form of diarrhea not to be confused with real writing‘.

We’re reminded just how harsh some artists can be toward one another. How competitive. Egos perched and poised at the top no matter how briefly, protecting that pinnacle from those efforts of all comers with scathing barbs and spiteful quips that in many instances develops into an adversarial feud. Authors and artists clambering for recognition, for news-making headlines on the premise that any publicity is good publicity. Marianne Moore on Lillian Hellman: ‘Every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the‘. Henry James on James Fenimore Cooper; Ernest Hemingway on Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, Sherwood Anderson, etc; Dorothy Parker on everyone. Matisse on Pollock; Picasso on Pollock. All of them brandishing and elevating their own techniques against presumed imposters.

If we imagine a trade utterly without content and drawn almost entirely from technique we imagine a stock broker. A day trader, lead by numbers and the instant gratification of buying low and selling high within the same day and nothing more involved in the depths of that pursuit than the satisfaction of a successful transaction. A profit. Or to a slightly lesser degree, an accountant lead wholly by the truth of numbers, with an eye on the bottom line, the solvency or insolvency of how those numbers add up but often with little concern or awareness for the flesh and blood of the business those number represent. The engineer, brainwashed into believing all the world’s essence is drawn from science; or the upstart indefatigable arrogance of a young techie in Silicone Valley dismissing virtually everything for the enlightenment of a product-driven industry that holds such advancements akin to the dawn of a new age.

We think of the trial lawyer. No less training in the fundamentals than the engineer or physicist or dentist and taught to follow the facts. To extrapolate the often confusing and purposefully misleading evidence against the presiding historical precedence of case law and eventually piecing together a defense that might, or might not, convince a jury of common layman. A jury of plumbers and salesman and secretaries. And how once he stands to address that jury and present his final argument, what surfaces is of another mandate. A mandate separating Clarence Darrow from his peers. An ability to bring into the equation whatever Clarence Darrow possesses in presenting the evidence with a humanitarian flair, with the spirit and soul of an artist. A performance, in guilt or innocence, that can influence others to an extent they are visibly moved. Transformed by the sheer power of his content, of his essence, of his intuitive sense of crafting his argument with all the innuendos and nuances and syntactical wizardry that will reach deep into the reasoning hearts of a plumber, or salesman, or secretary who will ultimately decide the fate of the accused.

The issue encompasses almost any pursuit. Including athletes. In the beginning you study technique, absorbing the preaching and tutelage of your early coaches and studying the live-action rhythms of those in the sport you admire most and of course you read everything written on the techniques of, say, well . . . pole vaulting. But at some point along the way, a great pole vaulter must discover who he or she is. What is it that they bring to the sport beyond mere technique? Or the high jumper, as in Dick Fosbury who introduced the Fosbury Flop in 1963. The high jump bar for Fosbury was the same bar that hundreds of thousands of athletes had been competing with for eons, but Fosbury carried the known technique into the stratosphere and came back to earth with something unrecognizable, that just happened to reward him with an NCAA title and later, an Olympic gold medal. He familiarized himself with the known techniques, searched himself, and made improvements that in turn improved the content. Fear of failure doesn’t exist. Failure itself was a part of the growth process–accepting it, embracing it, and benefiting from it.

Most of us bring nothing to our impassioned interests beyond the known instructed techniques. A flawless technique, at best, worked and honed to perfection. A technique that was developed over far more hours of practice than allows for the intangible search of some inner self. Some inner self that might of course be the catalyst for redefining the medium, or not. That might result in the Fosbury Flop, or redefining the historical designs of a racing sloop by relying on the novelty of physics and the insightful aerodynamics of a luffing sail. The innovative boat designer serves his apprenticeship and ultimately searches the limits of what exists in the chance of redefining the genre while securing his place among the competitors. A means of garnering business and the solvency of a profitable business that was built on a reputation for innovation.

A novelist searches for a voice that will distinguish him or her in the same way as the boat designer strives for the signature of a unique hull. The search itself, the willingness or compulsion to traipse down that rabbit hole offers no guaranteed returns beyond the time spent. Lessons learned and data gathered that will be put to use in succeeding trials until ultimately the writer’s voice surfaces. The rhythm of his or her sentences and the pace of his or her thoughts as a recognizable imprint. A search that for some, by the way, can take decades. But without it and you are simply transcribing the English language into ideas that have likely been said before and will be said again. Or, as a woodworker, you are simply re-creating pieces that have been replicated ten thousand times before. Not wrong, but not all it could be. You are focused on technique, because technique is safe. Technique has rules. Content does not; content is the artist’s interpretation of the known world and there is no guarantee an artist’s insight, or content, will pass the mustard.

In some corners of the studio furniture industry there exists a genre for furniture as art. By that we mean furnishings that are far more visual than functional, and in fact in many instances, virtually useless toward any practical purpose. Although the genre has many critics, both within the field, and at home, where Mr and Mrs Doe have an understandable fondness for a dining table that won’t have their Sunday stew sliding the length of the table into Mr Doe’s lap. But if we consider how, among these works, good sound, even flawless, technique is not only prevalent, but a mainstay, then we witness a work that has graduated from the confines of technique into the unknown of content by redefining the aesthetics, and in many cases, even the techniques themselves. The results become subjective; they are now open to the criticisms of an all together different medium. The medium of art, judged and weighed and assessed and anointed with a level of harsh cruelty, or gushing admiration. The division between technique and content has been breached and the precision of hand-cut dovetails takes a backseat to the same overall impact of a painting. The technique of the dovetails, or brushstrokes, remains important and crucial to the artist’s credibility, but the work as a whole has been thrust into the realm of subjective analysis. The woodworker who once replicated 17th century highboys with a dazzling precision of his or her workmanship, is suddenly no longer being judged solely on those techniques; he, or she, is now vulnerable to a much harsher consideration. Does this unique vision as a work of art, a signature content, speak successfully to the bricklayer, the secretary, the middle school principle, the professional critic?

Does such a phenomenon exist in all pursuits? Is there a level of performance and accomplishment residing in the depths of anyone who strives for excellence? A decade or more ago I was at the San Francisco opera, thumbing through the program during intermission to such an extent that I was actually reading the orchestral credits. Among those names was one I recognized. A peculiar name I hadn’t heard nor seen since I was five or six years old. After the production I gave my card to an attendant at the stage door and several days later I got a call from my old playmate. Billy, as I remembered him, but William now. The co-principal of the horn section. The French horn. A job, complete with benefits and sick days and vacation time and even a pension. His brother, Joey, I learned, played for the symphony in Geneva, Switzerland. His sister for the Chicago symphony. What I remember, when prompted, was the countless hours as kids in Champaign, Illinois. The brothers and their sister and myself and my sisters in numerous overnights and living our afternoons at the Country Club pool in the summers and at the toboggan run in the winters and, upon some further reminiscing, the memory of those days punctuated by two hours a day of piano practice.

Our grandparents had been close. Our parents had subsequently been close. And then the six of us, the youngest of that continuum, and all of it ending rather suddenly when my father died and my mother shocked everyone by moving us to the tranquility of the country. Much later, decades later, I understood the decision was necessitated by a need to separate one phase of my mother’s life from another. Thoughts, all of it, returning with this chance encounter at the opera 50 years later and the resulting re-acquaintance with Billy. A friendship that did not resume from where it ended as six year olds. We passed news of our siblings and learned his surviving mother continued to visit annually with my surviving aunt and eventually talk of opera itself. Of the legendary singers who performed with the San Francisco Opera and how each of these renowned divas tended to interpret their roles with a distinction that required from the orchestra something more than the familiar notes on the score. Notes played with a precision that began , in Billy’s case, with two hours of piano practice daily since he was five years old. The rigid and unrelenting strictures of a known composition performed by orchestras around the world for centuries. The disciplined, flawless technique of a musician performing at that level who must adjust such technique to the whims of a visiting Rene’ Fleming and her powerful interpretation of Violetta in La Traviata. This, I came to understood, was what distinguished those among an operatic orchestra from all those who simply played the same scores without error. The ephemeral knack for sensing and anticipating the signature pauses and sustained octaves of all those visiting sopranos performing all those solo arias of all those operas with an intuition that insured the french horns or the oboes or the violins performed as accompanists, in sync with the brilliant peculiarities of all those marquee talents rotating through any given season at the San Francisco Opera.

Would the same hold for a symphonic musician who plays the scores as they were composed and not to the nuances of a visiting soprano? Would such a career require from the musician something inherently different than from the operatic musician? Billy’s wife, as it happened, had been a member of the San Francisco Symphony for 25 years. The two of them and their children living a nice quiet life out in the Sunset district, 15 minutes from both the Memorial Opera House and Davies Symphony Hall on Van Ness Avenue. At a performance of Opera in the Park one year my oldest sister and I had a chance to meet her, and by comparison Billy, or William, had all the characteristics of an artistic temperament. A temperament normally obscured by the working uniform of a tuxedo and tails worn by all the members of the orchestra, and yet the peculiarities leaked through. At the intermission, visiting on the grass at Golden Gate Park, he asked for several phone numbers and we were startled how, in an era of the ubiquitous cell phone, he drew from his breast pocket a sheaf of tiny note cards, each of them with names and phone numbers. He leafed through them one at a time, squinting at the entries written in a tight nearly illegible script. Eventually deciding by some organized code which card was appropriate, he stood with his pen poised and we dictated the information and then he returned the whole packet back into his breast pocket. We didn’t bother to ask why he hadn’t entered it all in his cell. Or at least an address book, arranged alphabetically.

A small but telling glimpse into William’s personality that allowed him the resiliency of anticipating all the idiosyncrasies of all the tenors and sopranos in a career decidedly different from that of his wife’s career who, on the weight of this one introduction, appeared as the stabilizing measure of the marriage.

While back east studying at North Bennet Street School, , Ben furthered an appreciation for Sam Maloof, a west coast woodworker who at the time was in his early 80’s. A self-taught woodworker whose signatory work is the Maloof rocker, selling for about $20,000 each and backlogged about five years. To Ben’s instructors at school, Maloof’s name was met with some complacency, and although they admired his gift for design and style and having rearranged the course of furniture design itself, they were unable to get beyond the methodologies of a self-taught woodworker who was not opposed to the occasional screw in lieu of a wood joint. Or to his abuse of the accepted safety standards of the bandsaw. This would be the two worlds of woodworking meeting head on: the school whose only identity is to adhere to the strict principals of woodworking fundamentals, practiced exquisitely, we might add, on replications of furniture designs that had been around for centuries. While the aging Maloof, with his eye on the end product, strove for the rhythm and aesthetic impact of an end product and what he must do to achieve that. The joinery and technique become a secondary and subservient faction of the greater whole (Assuming of course that the techniques are functionally stable and secure).

In the world beyond artists and craftsmen, the issue is as recognizable as the paint-by-numbers approach. And although not termed Content nor Technique, the same propensities are at work that prevent us from acting on instinct and intuition and wallowing instead on the safe turf of a deliberating process. The deliberating process, at its most elementary level where our canvass arrives in full outline and color-coded by numbers delineating what color to use and we are free, utterly free, to focus on nothing more than painting between the lines. Even a coloring book leaves the choice of color to the child’s discretion.

I have a friend who met a woman. A friend who has known a number of women over the course of his life and who doesn’t regret having known any of them. To some of our mutual friends, he suffers from a lack of commitment. An inability to settle down. A preference for playing the field. Considerations, I might add, held by those who long ago settled down and abhor the very idea of being thrust back into a world where the search begins anew. Their relationships are safe and in place and although they are often not particularly happy, they nevertheless belong to a known world, whereas the known world of our mutual friend is forever being redefined.

He meets his newest friend and because he has experienced what to some are considered an endless strings of failures, his parameters in the art of love are somewhat more advanced, more demanding. In his own estimation, his earlier loves are not failures, nor were they ended with the slightest hint of animosity. They were explorations and stepping stones, experienced with full immersion and resulting, each of them, with a redefined approach to love. A technique, love, that can be furthered and polished and honed and although sharing the same basic fundamentals as any union–devotion, loyalty, companionship, passion–it is embellished with an array of nuances and techniques that, as such, elevate it to an art. His particular love, let’s be clear, is not necessarily better. It is fundamentally different.

It is the difference between composing a piece of music based on the known 12-bar blues riff and a Mozarian symphony. Both are, per say, composers and can introduce themselves as such in mixed company. But the similarity ends with that title. One has undertaken a far more complex approach to excellence, fraught with endless failures no doubt, but with each failure what develops is a more versatile and capable content. And culminating from a lifetime of such progressive failures we arrive at a strata of completeness otherwise impossible to achieve or possess. Reaching, in a forevermore compulsion to quench our endless curiosity. Picasso gravitating from realism to blue to cubism.

My merely dictating a premise like a parent pointing a finger at the traffic in the road and wagging it at their toddler with the No No No goes only so far without an example of what sort of damage a moving car can do. So we keep serving up examples, as if offering metaphors for a thesis that is simply too complex and extraneous to illustrate with a preaching finger wag.

As a 12 year old I was sent off to Camp Paddle Trails on the Oklahoma/ Arkansas border. Three glorious weeks away from sisters, wallowing in a boy’s life of canoeing, horseback riding, leather-crafting, ham radios, swimming, woodworking, and the endless pranks of boys being boys. At the end, on Parent’s Day, my mother and sisters arrived to watch a series of competitions and most notably my own entry into the high dive. The cliffs off the Illinois River from which we leaped with some form or practiced technique. Just two of us left in that competition, diving for the gold before a crowd of perspiring onlookers to watch my opponent perform an exceedingly simple but flawless swan dive, and to watch me perform an exceedingly difficult but flawed 1-1/2 dive. The dive requires a rigid 90-degree jackknife, a full 360 turn and an unfurling entry at 90 degrees to the water with ankles closed and hands opened flat. I was less than perfect. I had no expectations of being perfect. Following my performance I swaggered from the river to where my sisters and mother sat in the sweltering Arkansas sun. I stood for a moment, proud of my dive regardless of it flaws, beaming, dripping wet, not so much expecting their kudos as a means of pronouncing my boyness in a world of women. My mother dabbed her forehead with a monogrammed handkerchief while my oldest sister’s gaze was leveled on my tent counselor, the 17 yr-old Jerry Hall who stood across the meadow returning her gaze as my middle sister, a horseman, sat watching the swayback mares of the camp stables grazing in the distance and eventually I turned to my youngest sister, my unfailing 7-yr-old ally who by then was on her knees in the grass picking her fingers curiously at the several black slimy leeches fixed to my ankles. Proof I had been to the muddied depths of the river, and back.

Okay. Impressing my mother and sisters had become, long before Camp Paddle Trails, an increasingly difficult and pointless pastime. The others, all the others in that noonday sun, were wowed by the risk of my dive off a granite cliff 20 feet above the water. But my own brethren sat unimpressed, practically yawning, bemused by the leaches as if they were the crawdaddies that inhabited our own river back on the farm. The leeches . . . well, I’ll be honest; an iniquitous little staged performance on my part to purposefully languish on the river bottom until I felt their tickling presence fixed to my ankles and then purposefully, insistently, slyly, leaving the river and approaching the four of them in yet another performance in a life of such performances with the sole intention of soliciting a little shock and awe. But of course they all played their own performances, long accustomed to my infantile means and with the exception of the youngest, they sat with a bored nonchalance. A practiced indifference in a family raised less to the achievements of any governing body than to the standards of our own inventions.

My sisters remain to this day my harshest critics. The oldest, the marketing director of a Silicone Valley firm, reads through something written and rather than discuss any content or potential impact of the work, we spend an hour dissecting the proper or improper usage of allude and refer. The middle sister, who founded a geological firm in Portland, OR, equally impervious to content, questions the sequence of any events and the truthfulness of my interpreted memory, and the youngest, a lawyer and engineer, well . . . the youngest simply laughs, assuming there is no truth whatsoever in anything I write. They are all correct, of course. I stretch words and purposefully mangle their roots until it serves my usage; I embellish leaches to serve a point; I am less interested in the definable, unwavering alliteration of events than the impact of their collected summary.

There were 72 campers on the boy’s side of the river and 75 on the girl’s side and I am about to embark on a story my sisters have all heard a thousand times. In it’s various reiterations. Near the end of my stay at camp we were given a choice of a 4-day canoe trip or a 4-day horseback trip. To qualify for the canoe trip the boys had to leap into the river fully clothed, strip naked, and climb into the awaiting canoe stationed in the center of the river. Dressed then as now, in heavy Levis and high-top converse, this was no small feat for the boys, whereas the girls had the advantage of light shorts and low-top sneakers. What I recall is having the converse unlaced and off before I sank to the bottom of the river, sitting on the bottom wallowing in the mud as I worked to blindly removed the heavy denim Levis one leg at a time. The denim was of course wet and clung to my legs and once they were unfurled to gather at my ankles, I then lost the use of those legs in the event I should quit and need to make my way to the surface. On the bottom, utterly blind in a river the color of molasses, running short of air, wrestling calmly with one leg at a time, I managed to maneuver the last leg over my heel and make my way to the surface gasping desperately for air. Among the 72 boys, I was the only one to manage this feat. The only one. My reward? A four-day canoe outing with 13 twelve-year-old girls who sloppily banged their paddles against the canoe with each stroke and whose idea of a paddling technique was to skirt the blade against the water in a splashing circumference of giggles and yelps. A prison sentence. My worst scenario. Even the accompanying counselor was female.

My own technique with a paddle was near perfect. A young male egoist’s assumption, grasping for some superiority, some distinction among this feminine majority. A stroke that was rhythmic, efficient, and with good tempo–something I had practiced earnestly for two weeks. A technique, once established, that freed me to employ the ensuing content of four days confronted with an infinite variety of rapids, currents, and the ever-changing bends in the river. But harnessed, I tell you, by the clanging banging paddle-blade of my canoe mate stationed on the bow undoing my every effort to steer us accordingly. A prison sentence . . . until by the second day I understood my days of boys among boys had effectively ended the day before and I settled into what I knew. The known parameters of a known world. I took up the splashing excursions and joined in on the campfire songs with a few guttural registers and devolved into the precarious act of ribbing and teasing without hurtful intent, and came to know Lilly. Lilly, the youngest and only girl among four brothers back in Mississippi.

1962–Kamp Paddle Trails

1962–Kamp Paddle Trails

Awarded the Kamp Paddle Trails medal

Awarded the Kamp Paddle Trails medal

Inscription: ‘Best Camper 1962’

Inscription: ‘Best Camper 1962’

1962-Charles’ hard-to-impress sisters.

1962-Charles’ hard-to-impress sisters.

John Houston, the late film director, when asked what he most wanted out of life responded with: ‘For life to remain interesting.’

Allowing a moment for such a simple response to settle and take hold, we understand that without interest, there is nothing. There is no hope, no industry, no challenge or the wherewithal of what might be. There is only chronic dullness. The most ineffable dullness. There is nothing interesting about a swan dive.

If there is one arena in all of human nature where one must certainly rely on one’s instinct and intuition (i.e. Content), it is in the presence of love and affection. And yet it is alarming just how many of us refuse to acknowledge the fluttering heart and the tingling goosebumps on the back of our necks for the concreteness of what can be defined. Love is not definable. If it were there would be entire bookstores shelved with manuals of the step-by-step process required to achieve such a state in the same way as succeeding in business, or money management, or learning to pole vault. And although the old premise of saving oneself for that one true love remains as a guiding light to so many, the truth is it denies us the opportunity to practice and rehearse and hone our techniques toward experiencing the fullest love. A lifetime of pent-up sincerity and the most earnest intentions rarely supplants the advantages of a little polish and experienced technique. Love requires repeated leaps of faith into the unknown, weighted by a host of variables like our own good judgment and an understanding that certain protocols are in order and the amour of an undaunted optimism in the presence of failure. To have failed, to have botched your courting process with a blundered quip or the uneasy awkwardness born from the rarity of the experience and to subsequently withdraw from a fear of further failures would be like Fosbury withdrawing from his early accepted techniques and denying us all the pure exhilaration of watching that phenomenal Flop. That Fosbury Flop.

Content, as a subjective state of intuition. An acquired state, we might add, developed and honed like any aspirations toward excellence. Gathering repeated failures as a learning reservoir. A life where the sights are set to a more encompassing scope. An overview, of sorts, that acknowledges the details and processes of technique within a peripheral vision that is far more concerned with how those are employed or melded into the overall scope of an intuitive decision. On this scale, technique itself becomes the minutia that simply fuels the engine of what we are and hope to be. Without that, without that engine, or vision, and the minutia quickly and easily dominates our content like a blue-collar bully dismissing the intangibles of our spirit as if it were something to ridicule. We peruse the potential mate for the fundamental attributes of careers, financial solvency, hygiene, attractiveness, and even genealogy as if checklists on a bucket list, while refusing to wholly trust the heart, the intuitive soul of a decision that will play out over decades as the lasting foremost truth.

So we’ve somehow progressed from furniture-makers and artists obsessed with technique at the expense of innovative content, to the visionary who understands that technique is a learned skill within the broader scope of perhaps an unimaginable achievement. A learned skill, as in almost anyone with a desire and discipline can learn the techniques of wood joinery or grammatically correct sentences or playing a musical instrument and even do so at the highest level, but they are skills. They are techniques practiced and practiced and honed to a professional perfection, whereas without content, without vision, they become a life of practiced discipline. The bucket list that supplants the quest for love against the more ephemeral considerations of love itself.

The novelist or poet who begins his craft with an almost obsessive focus on the rules of their genre is a common malady within the hundreds of popular MFA programs offered by just about every university in the country. The more talented graduates of the better-known programs write with an enviable tightness, a workshop succinctness to their structure that is much appreciated by the reader who has no patience for a lazy sentence. If the talented graduate happens to also have an ear for rhythm or cadence with his or her words, then we have a work that is not only well-written, but with a musicality that reads with the same intonations as if listening to a sonata at the concert hall. All fine and well and a level reached by only a few, but given those few and we see that few of them have been schooled or practiced in the broadest scope of a real and purposeful theme. A theme reminiscent of, say, To Kill A Mockingbird, in which Harper Lee lacks the tight, learned, succinct and imaginative techniques of her childhood and lifelong friend, the stylist Truman Capote, but instead brings to her masterpiece novel a much nobler cause of the larger theme that serves to ultimately change our lives.

Capote was a writer. A gift bestowed upon him for the rhythm of words. An appreciation and love for the sound and arrangement of words and, well . . . we might as well state that it was also a full-blown, obsessive compulsive addiction for the minutia. Separating him from others equally afflicted was this dexterity I might compare to Picasso or the Beatles or Frank Lloyd Wright, all of whom progressed over the course of their careers to repeatedly redefine themselves. So gifted within their respective mediums to have bored themselves with perfection. And instead of planting themselves in this comfortable, albeit rare level of performance, they reached into the depths of their souls, the content of who they were, and shuffled the cards to resurface with the same affliction for unparalleled technique but on a wholly new platform virtually unrecognizable from their previous incarnation. And they did this repeatedly throughout the tenure of their careers. Capote debuted with the baroque symbolism of Other Voices, Other Rooms, followed by the enormous success of the theatrical The Grass Harp. Serving notice early on to expect the unexpected by going on to present a leap into the dynamics of a bold characterization of Holly Go Lightly in Breakfast at Tiffanys, followed by the cold, impertinent reportage of In Cold Blood, followed by the gossipy dialogue of Answered Prayers and finally the deep resonating essays of Music For Chameleons. Seemingly, five books written by five different authors, but with a commonality drawn from Capote’s flawless and highly developed ear for the rhythm of words.

A more familiar extrapolation would be The Beatles? The early innocence of I Want To Hold Your Hand to the maturing Rubber Soul to the shocking leap of The Magical Mystery Tour to the complexity of The White Album to the full scale cultural transformation of Let it Be. No one listening to the early music would recognize the latter efforts as from the same source. A transformation of degrees with the continuity of gradual but persistent steps away from what once was to what will be. The album Let if Be could not have been achieved without the progressive beginnings of I Want to Hold Your Hand. To skip that apprenticeship, that early process, and leap directly into the White Album would result in the barn-like canvasses of Mr Pollock, mastering the technique of pouring paint from a gallon bucket. A technique, no matter how self-elevating it might seem to Mr Pollock, exists as an elementary devise that resists even the most perfunctory scrutiny.

Perhaps less familiar than the progression of the Beatles is the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. A masterful self-promoter, he imprinted a style of residential architecture in Oak Park, IL that came to be known as the Prairie Style, with its blockish muscularity of low-pitched rooflines and wide confident eaves punctuated by strong horizontal planes. Although developed originally by his earliest mentor, Louis Sullivan, it was not fully realized without Wright’s rendering that catapulted him into the darling of American architecture. Followed by a period of darkness and personal loss only to reemerge with the likes of the textile registry of The Unity Church and the Imperial Hotel and The Biltmore Hotel and again, followed by horrible personal tragedy and seemingly inescapable darkness to leap back with the thoroughly modernistic Johnson Wax office building and the Marin County Civic Center and finally, finding peace and contentment in his 80’s, providing the archivists and historians of the genre with one of the most enduring and mesmerizing anecdotes leading to the creation of the most noted piece of residential architecture in the entire world.

The iconic architect, at 67 and wallowing in one of the aforementioned dark phases of his life, was approached by the retailer Edgar Kaufmann with a commission to design a residence set amidst the pine woods of southwestern Pennsylvania. On a subsequent visit to the site in November 1934, Wright requested a survey showing not only the elevations, but to include the placement of every tree and every boulder as well as the topography of a babbling brook that was to be central to the residence. Over the course of the following ten months, Kaufmann made several entreaties to learn the progress of the design and each time was dismissed with an assurance that things were ‘ . . . coming along nicely.’ But in truth, not a single line had been sketched. Finally, growing concerned, Kaufmann called one morning in September of 1935 while in Milwaukee on business and expressed a desire to make the two-hour drive to Taliesin East, Wright’s noted home and studio in Wisconsin. Wright said fine ‘ . . . we’ve got something to show you.’ While in truth he had nothing whatsoever.

According to a number of nervous apprentices who were eyewitness to the events of that morning, Wright turned to a blank sheet and calmly over the next two hours drew the plans in the time it took Kaufmann to drive from Milwaukee. Not just the house, situated directly over the waterfall instead of Kaufman’s original request that it be below to afford a defining view of the site, but to include in his sketch every boulder and tree accurately placed without consulting the site survey. Mr Kaufmann arrived and was ushered in to the studio where Wright stood, solicitously offering the completed design as if it had been ready and waiting for weeks, or perhaps months.

What we learn from these accounts is that Wright was not actively drawing and sketching his way through the various permutations of the final result. For 9 months the project existed solely as a cerebral entity, a daydream mulled over during lunch or breakfast or sleep until the building image culminated in his mind and all the doctrinal of the supporting details were present. The drawing itself, at this juncture, was almost perfunctory.

Had he spent those succeeding nine months creating draft after draft of a learning curve toward a satisfactory end, he might likely have become consumed with the assorted and accumulated details rather than the more encompassing impact of the primary overview. He avoided allowing the technique from bullying the more effeminate content. The technique . . . well, the ensuing hurdles of actually building a house on top of a waterfall, complete with what at that time were the usage of innovative cantilevers and reinforced concrete would prove almost insurmountable and return in the form of present-day retrofitting and structural renovations that to some are the shortcomings of such innovations and to others, simply the pratfalls of any continuum that departs from the known mold.

Wright, Capote, Picasso, and the Beatles are representative of the few, the very very few artists who have created an original content that was both unique and signatory, and then proceeded to redefine that content into a new form nearly unrecognizable from the original. We see that linear growth of repeated invention can only be appreciated and acknowledged once the full canon of their work has come to an end. Only then can we trace the growth from start to finish, from Picasso’s Realism to his Cubism, and hope to make some sense of why and how he possessed such a grasp on his own spirit or soul or peripheral chemistry when others, the rest of mankind, wallow in the technique and the dogma of defining even a single signatory style or voice.

What is it that separate them from all the others? From the Hemmingways, who created a distinct minimalist voice that resonated through the literati for decades but was essentially unchanged from his first book to his last. Or the Mozarts and Beethovens and Rembrandts who were prodigies of enormous talents and whose work will never lose its influence nor impact on succeeding generations, but whose techniques, or signatures, are constant and recognizable throughout their careers. And is it a good thing? We don’t seem to be able to get enough of Mozart as it is; why would we want less of what we have in lieu of a second, or third, phase unrecognizable from what we’ve come to love and appreciate?

Clearly, their professional development ran parallel to their personal growth; their lives were forever changing and morphing with not only an open-mindedness to such change but perhaps an insistence upon it. Physically, as in the aesthetics of their actual personal appearance, the change or transformation is noticeable but not defining. Noticeable by little more than the advancing years of age; Picasso’s stance, the epitome of confidence bordering on arrogance was the same in early photos as in old age. A little less hair and a more rounded physique, but otherwise no redefining or purposeful aesthetic presentations. Frank Lloyd Wright shows us the same insolent eyes at 25 as 91, and only a few alterations in his dress code over 6 or 7 decades. Capote presents a distinction of being openly gay at a time when homosexuality was deemed with far more trepidation than today, and yet rather than mask that, as did Somerset Maugham or so many others, he embraced it with, on the one level, an appearance that at times mocked the existing social mores and attitudes toward gay men. Furthering that with a pattern of speech so affected it became performance art to a level that elevated him to the talk-show circuit as if an attraction at the local carnival. Possibly the most succinct show of changing appearance and changing output were the Beatles, who must be remembered as cultural light posts as they were artists. The change in their personal appearances and dress codes and socio-political positioning mirrored, or helped initiate, an era whose growth and transformation through the cultural revolution of the 60’s and early 70’s was so prevalent that they could be considered the textbooks for a generation desperate for the answers of a new age.

But by and large, there are no clues nor defining links between the physicality of appearances and the fruit of one’s endeavors. The fruit is too deeply embedded for the distractions or superfluous veneers of physical appearance alone. A malady so commonly witnessed that to so many, the threshold into art begins with a dress code. A dress code drawn from a cliche of assumptions such as donning a beret or even fixing to one’s self-identity the salutation itself of being an artist.

All of the above were masterful self-promoters. With good reason. We say, or hear it said repeatedly how an audience to a true artist is of secondary concern and that the work itself has always been and will always be the compelling reward. A dictum never better illustrated than with Vincent Van Gogh, whose works never earned a dime in his lifetime. A lifetime, we might add, that existed in a state of perched anxiety and insanity. But the more reasonable and frankly, truthful, admission is that an audience is and will always be an essential ingredient to the driving stamina of any imaginative, innovative, creative process. And to maintain an audience, to keep an audience won over by early debut works requires a showmanship of educating that audience in the acquired appreciation for how to accept and appreciate the Unknown over the Known. The enigmatic personality of a Dali Lama or a Lincolnesque disregard that is played with a masterful subtly to accumulate and amass a following who become addicted to the changes of their guiding light. The resiliency of such lives and how that can define the open-minded resistance against the dreaded existence of a perpetual inertia.

A required role, we’ll add, for our above examples but not so much for the survival and expansion of an unchanging work. We look upon Dustin Hoffman or Charlize Theron or Christian Bale, even Meryl Streep as extraordinary talents with a versatile range that seems without limits. We never know what to expect from them, and have come to expect and accept anything. The dexterity of these performances is marvelous, but is distinct from the linear evolution of those who mature with a gradient that never looks back. We stay with Mr Hoffman because we know we’ll be rewarded with a brilliant role, whether as a downtrodden Ratso in Midnight Cowboy; a cross-dressing Tootsie; the disabled Raymond Babbit of Rainman; or the reserved Ben Braddock of The Graduate. We stay with Picasso or the Beatles because we believe we are being educated to appreciate something beyond what is known. The unfurling into a linear redefinition that will not bounce about like a pinball careening from genre to genre.

The initial instinct of an audience is to resist being educated. To occupy the comfort zones of expectations and known entities. The opera banks on the recurring productions of a host of classics like La Traviata and Carmen and the theater, Broadway, with the endless revivals of Oklahoma and Noises Off and Porgy and Bess. The New York Times bestseller list is populated with easily digested titles, as are those films offered at the local theaters and the mimicking sitcoms and reality shows on television. The painter Thomas Kincaid made millions by repeatedly providing his audience with scenes depicting simple dreamy cliches. Defined, all of them, by a technique that predicates a form with the primary objective of satisfying the expectations of an audience who resists change.

In 2005 I spent 5 months in Andover, MA. A long way from Sonoma County, both geographically and culturally. A part of the country, New England, that had long been a slight to Prowell Woodworks. We hired an Operations Manager and added a shop south of Boston and made something of an assault against a history of lackluster interest. In my time there, I made a few discoveries. Insights that had nothing to do with our product lines and everything to do with a culture based on status quo. The stoicism of resistance to change. A culture that was largely Colonial in their preferences for architecture, which translated into the prescribed and acceptable options for colonial furnishings and colonial landscape designs, but was furthered with this indescribable, utterly perplexing phenomenon of a dress code first introduced to American fashion in the early 1950’s. Penny loafers, without socks. Casual blue blazers and pressed denim jeans. Teens in school uniforms of polo shirts and blue blazers pasted with the school’s crest. A clear and definable dress code born from 50 years before as a means of establishing one’s place within a known identity as well as accomplishing the safe expectations of a paint-by-numbers acolyte.

Our persistent poor showing in New England was and is the result of a culture rooted in history. The safety of an outlook that prizes a resistance to change and the opposite of an audience who appreciates and seeks innovation in both technique and content. An area that is, oddly, politically liberal, and yet culturally conservative. An area that is, culturally, 180 degrees from northern California’s Sonoma County.

In searching for craftsman during my stay, I discovered no shortage of production shops and very few one-off craftsmen. Artists. The production shops were confused by the designs and how the complexity of those designs could be managed in a production-minded process. A trend that went much deeper than I might have imagined; for two hundred years Massachusetts had been defined by factories manufacturing everything from musket balls to shoes to colonial furniture to textiles. Mill towns, scattered all over the state, situated on the endless little waterways. Mill towns, to a Californian raised on a farm in Illinois who had never in his life known a single person who had ever worked in a factory. Generations and generations of mill town descendant’s bred to resist anything but the status quo of their own history.

Charming brick factories with their historical waterwheels sitting empty as a testament to an economy that had moved on in the late 70’s and left in its wake hundreds of adorable yet depressed towns with boarded-up down main streets and a constituency content to live on the dole. A trend that began with the furniture industry migrating to North Carolina in the 1970’s and progressed with the apparel industry moving to Mississippi and eventually furthered by Reaganomics in the mid 1980’s that saw a mad flourish to outsource everything overseas. A quick injection to the GNP, we might add, but a devastating impact on local economies that has never recovered and largely responsible for the teetering state of the American middle class we know today.

Kind people. Pleasant, gracious, accommodating descendant’s of the Commonwealth. A populace who might have registered the merits of a Picasso, in Picasso’s time, with the same resistance as Arkansas, or North Dakota. A culture with the genetic definition of administering techniques in a repetitive and redundant approach–button factories, shoes factories, Windsor chair factories–that precluded the slightest hint of innovative content. Pushing the bar. Furthering the compliance to this Known existence to a level of critical thinking required for not only the revitalization accomplished by North Carolina in stealing away the furniture industry, but the sort of critical thinking required to engage in an interesting and insightful conversation.

Igave up and left New England to the New Englanders. Returning repeatedly since then to simply appreciate the landscape and the charming drives and the picturesque villages, and the seemingly stable infra-structures, but never with any expectations of winning their patronage. A patronage that after nearly 40 years in business is drawn almost exclusively from a demographic that is educated, liberal, affluent, and with the flexibility of recognizing and appreciating the impact of progressive content.

There are thousands of towns in America identical to the withering mill towns of New England. Although not given to the manufacturing history, they exist along the byways and blue highways of all those states where our products are dismissed with an overwrought artistry. A consummate road tripper who enjoys meandering through these regions lost in time, I have witnessed the same scenes throughout the rural Midwest, mid-Atlantic states, the south, the plains, virtually everywhere defined by conservative politics and depressed ambitions. A regionalism characterized by the overriding truisms of a downtown long-ago boarded-up in lieu of a Wall Mart situated in the county seat. A big box shopping center cluttered with Target and Home Depot and all the same box outlets and within striking distance a scattering of pseudo gated communities with a faux California architecture and a golf course and a need to hug the shores of a watered-down economy based on anything but authenticity.

How do I appeal to such a culture? How do I incite some interest in our work to an area, if considered by land mass alone, dominates the map of America? More importantly, how do we convince them to withdraw from a dependency on a retail environment born from not just off-shore manufacturing, but accompanied with lower quality products at a bargain price-point. How do we convince them that paying more for their shoes at a local shoemaker’s shop is better. The shoes are better, but the long-term results of the shoemaker spending a portion of his profits with the local dressmaker, who in turn invests in lunch or dinner at the local eatery over the fast food chains. How do we circumvent a trend put into place 40 years ago now that has drained the life from all those towns and the resulting national economy in lieu of a misleading GNP spiraling upward on the backs of not only those who actually own those big box chains, but those investment shareholders who piggyback those profits. The profits of a single ownership, such as the Walton family of Wall Mart, who do not scatter their proceeds within these local communities. Who instead harbor those profits from a Texas stronghold in a manner that, on paper, appears to the economists as if our national economy is functioning when in truth it is not.

It would be pointless to sit on their front porches and engage in a conversation about an article such as this. It is certainly not my role nor purpose to convince anyone of anything political or moral. I am however drawn to what was once referred to as American regionalism. Those pockets populated by a continuum neck-deep in local descendance existing outside the known trade routes that not only drive the economy, but that fail to attract newcomers. New blood, educated elsewhere, raised elsewhere, relocating in a re-population and revitalization of places like Raleigh-Durham, NC with its promise in the early 1980’s of jobs and growth and the growing strength of like-minded transplants that in turn spawned a second economy in the hi tech industry. Voile’: in the span of a single generation a forgotten pocket becomes a hot pocket. Locally educated and trained young adults elected to stay, to live out their lives and raise their own families in proximity to their parents, grandparents, siblings and the myriad social ties that result in the solidarity of regional pride. The generational continuum that insures the elders are looked after and the youngsters are the recipients of a great grandmother’s interest. A healthy and thriving regionalism is attractive to not only their own brethren, but encourages opportunities for young families relocating from California and Texas and Washington state, mixing up the bloodlines that in turn avoids the inertia of cultural stagnation.

Unlike rural Mississippi, where among the Caucasian population, the white population, there is a noticeable abundance of blond hair and blue eyes due to a culture that does not encourage or invite those from beyond that culture and where those within that culture are bred with such regionalism that leaving, relocating elsewhere, is largely unthinkable. If they migrate it is to Jackson, the state’s only city. A population of 175,000. A veritable megalopolis. An oasis of liberalism by comparison, landlocked on all sides and in every direction by the restraints of Arkansas to the west, Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, and to the south a blighted dead zone the size of New Jersey. A gulf that is the recipient of a Mississippi River depositing 1,500 miles of northern topsoil infused with nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers to spawn a sea of algae that gobbles up the oxygen at such a rate that nothing inhabits these waters that might constitute any sort of viable fishing industry (think shrimp).

Mississippi, with an annual medium household income of $36,000 and a per capita income of $19,000, is the poorest state in the union. A distinction it has held every year for as long as I have been alive. And we’ll add that among those bottom tier states are all those states previously mentioned bordering Mississippi. They are not investors. If they own homes it is because they inhabit the homes they were born into in an area where home values are by contrast ten cents to the dollar. They do not have investment portfolios mirroring the gleeful profits of piggybacking on the imbalance of the few who own the conglomerates now dominating the economy. They are by the very nature of their environment more concerned with the relevance of their existence than with any bigger picture regarding the world at large. It quickly becomes a moot point, and within minutes of being invited onto their front porches it becomes possible that maybe, perhaps, the content of life, the bigger picture, is not the same for all of us.

The family farm on my father’s side is in Harrisburg, Illinois. A southern Illinois where I spent meaningful chunks of my upbringing and where, later, I escaped to nearby Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. Jackson County, named after the country’s first populist president, Andrew Jackson. A county with an annual per capita income of $23K, with 28% living below the poverty level, and yet a high school graduation rate of 92% and 33% with a Bachelor’s degree. A confusing statistic: the high poverty rate coupled with the high education rate links us to the state of Mississippi where the tight regionalism disallows mobility. In the two tightly contentious elections of 2000 and 2004, Jackson county was the only county beyond Chicago’s Cook County to vote Democratic in a state whose electoral college has gone democratic in every election since Adlai Stevenson. Carbondale’s Jackson County, however, represents the apex of southern Illinois; the remaining counties comprise a regionalism every bit as poor as rural Mississippi and every bit as isolated from the currents and trade winds of anything economically or politically vibrant. Long ago, in my upbringing years, a land that relied on a thriving coal industry, a strip mining methodology that decimated the hilltops and polluted the waterways of arguably the most scenic corner of the entire state. But the coal dried up in the late 1960’s, and the economy spiraled. Permanently. A dead zone whose nearest metropolitan respites are St Louis four hours west and Chicago six hours north and Memphis 4 hours south and Louisville four hours east. A world, I’ll confess, for which I have the most profound reverence. A world I left two days after graduating from college and to which I wouldn’t return for another 34 years!

It was the tail end of a business trip to DC that found me renting a car and wandering through the rural backwaters of the Shenandoah and down through the Blue Ridge and over the Appalachians at the Cumberland Gap to track down a friend I had last seen in South America 30 years before. I passed through Lexington and the horse culture and detoured for a few photos of some earlier commissions within this enclave of high society before reaching the penurious hollows of Casey County. The poster child of American poverty with a per capita income of $16,000 where 69% of the population was on some form of welfare. A population of farmers nestled among the uncultivated wolds of an undulating acreage where my friend, a Brit, had eventually settled. Buying up acreage and hiring his neighbors in a breakneck effort to create an organic beef ranch. From a small modest little cabin and an original seven acres, he had expanded in just two years to hold the mortgage on over 1,000 acres, floating loans and borrowing from Peter to pay Paul in a frenzy of enthusiasm financed by a day job. A job as a computer analyst, a frequent flier of such that he kept a small studio two blocks from the Birmingham, AL airport. Running his empire on the weekends, returning each week with the knowledge he had learned from reading organic ranching magazines while sitting in airports and passing that information on to his neighbors who were now on his payroll and after just three days of wandering his enterprise and talking with his neighbors, I left. The clash of cultures was a carnival between my friend’s thick cockney accent and the slurred monosyllabic dialects of the locals that seemed doomed for failure on the grandest scale. With an absolute and utter unawareness of Kentucky regionalism, my friend had infused the entire county with a wild hope for something new and innovative. This flamboyant character who had left Brazil with a new Brazilian wife to return briefly to London to set off for the spoils of the Mideast to return to London to set off for an America riding the waves of the 1990’s boom years that found him easily winning over the tiny little bank in Liberty, KY with large deposits of funding borrowed elsewhere in this gravitating, magnificent scheme being played upon a constituency as vulnerable to hope as to the lure of a winning lottery ticket.

A week later and I paused on the banks of the Ohio River just downstream from the Wabash River and upstream from the confluence of the Cumberland and understood that from the moment I had left DC it was here where I would arrive. Stalling. Reluctant. An inexplicable nervous anticipation that had me pausing on the Kentucky side and even taking a room for the night before finally crossing over the following morning into a world I had always described to my sons as Heaven on Earth. The Land of Molasses n’ Honey.

I couldn’t remember, specifically, why I had left southern Illinois in the first place. A woman might likely have played a role. Or the vague reasoning of imagining a career in the southernmost extremes of an Illinois known for some odd reason as Little Egypt. An area of breathtaking scenery. Tranquil hills rolling through blowsy meadows and the light woods of Shawnee National Forest that was overlooked in Lincoln’s earliest campaigns as not worth the trouble. Renegades and backwoodsmen and southern. Wholly southern. Grits and spittoons and figures of speech rolling off the tongue like syrup. Later, in the 1930’s, it was here where Machine Gun Kelly and Pretty Boy Floyd and John Dillinger fled for the impenetrable cover of Little Egypt. Hiding out at an outcrop on the Ohio River known as Cave-In-Rock. A formation where the river pirates of the late 1700’s also bedded down, praying on the slow barges transporting armaments and supplies to the early French forts springing up in anticipation of the rumored acquisition of something called the Northwest Territory.

2004-Prowell reunited with his homeland

2004-Prowell reunited with his homeland

Visiting cousin Sally, seated in Charles’ great-grandmother’s rocker (Ma’s chair)

Visiting cousin Sally, seated in Charles’ great-grandmother’s rocker (Ma’s chair)

Carbonadale–With cousin Sally

Carbonadale–With cousin Sally

The original barn, still standing.

The original barn, still standing.

Big Ridge Baptist Church.

Big Ridge Baptist Church.

Big Ridge Cemetery.

Big Ridge Cemetery.

Carrier Mills–Boarded-up but for the Post Office and the one bar.

Carrier Mills–Boarded-up but for the Post Office and the one bar.

3-bdrm house. Asking 34K

3-bdrm house. Asking 34K

I wandered. Zig-zagging for days up and down and across the Shawnee National Forest, inadvertently following the old Trail of Tears footpath and along various Indian trails and the unpaved roads like BR110. The sprinkling of little communities, once thriving in my youth, with their downtowns boarded up for the past 30 years with nothing open for business but the Post Office and a single bar. Forever curious, meandering through the sparse little neighborhoods to pause before those homes listed for sale and calling the listed Realtor and shocked to hear asking prices from $11,000 to $34,000 in 2004–a full four years before the Great Recession. Charming houses on nicely maintained lots that at the time would be listed in Sonoma County for $600,000. In the end, I of course made my way to the farm where my father was raised and where we spent so much of our time as children and to where I later, in college, often retreated to the pampering and sumptuous southern meals of my Aunt Anna Lee. I explored the still-standing barn and strolled up the dirt lane to the Big Ridge Baptist Church, built on land donated by my great grandparents Ma and Dad, and wandered across the road to what I assume was the purpose of crossing into Illinois in the first place. The Big Ridge Cemetery. Here to commensurate with the tombstone of my father Jackie Dale Prowell, who left the farm to attend journalism at the University of Illinois and meet my mother and become the youngest sports editor of the Champaign-Urbana News Gazette and host a Saturday TV show interviewing the great athletes of the day and then dying, succumbing to melanoma at only 28. And the graves of his parents who succumbed to tuberculosis at 27 and 28. To consider the legacy and heritage of those descendants defining that farm for generations and generations until my graduation and a decision not to stay but instead move to California.

I look upon my own embellished memory of that heritage and those first twenty-three years of life so rooted and embedded in the long history and ancestry of my father’s southern Illinois lineage and my mother’s long and illustrious lineage within the country club culture of mid-state Champaign and I wonder if the trade for California, with it’s temperament for critical thinking and progressive natures was a fair comparison in the mind of a 22-year-old caught headlong in the rapidly changing world of the late 60’s and early 70’s. A fair assessment of what was being left behind in lieu of the modernity of moving forward. The historical, firmly embedded constitution of a status quo that focused less on reinventing oneself in an innovative march to somewhere, than the character of managing what is given. Managing the parameters of what exists. Enriching that existence as opposed to redefining it.

My entrepreneurial friend back in Kentucky was by his own definition all about content. His eye was on the scope of largess that dismissed technique with an irreverent shrug. The scope of creating something grand and innovative at a pace that left the locals dizzy with wonderment. A pace that out-paced whatever technical acumen he gathered perusing organic ranching magazines in the airports in the way Jackson Pollack disdained the tedium of realism for the antsy impatience of shear drama. But my friend was doomed from the beginning. A train wreck in-the-making. A cockney whose consonants came squirming off his tongue like melted train tracks married to his glamorous Brazilian wife from Ipanema who sunbathed off the back porch in her thong, the two of them like peacocks among the sparrows of locals whose own language was a minimalist’s mumbling monotone. The conversations of hand gestures somehow teaching the new organic techniques to those who had farmed that acreage with a generational continuum of protocols going back 200 years.