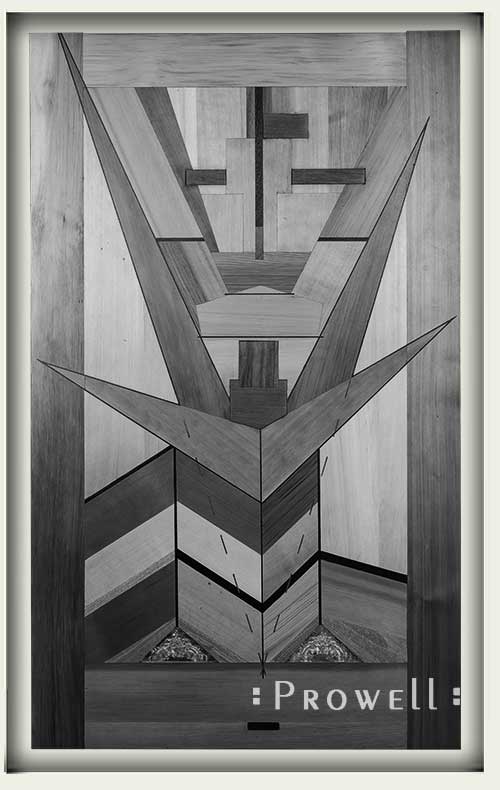

Not a garden gate design to be viewed and assessed in passing.

CUSTOM GARDEN GATE 217

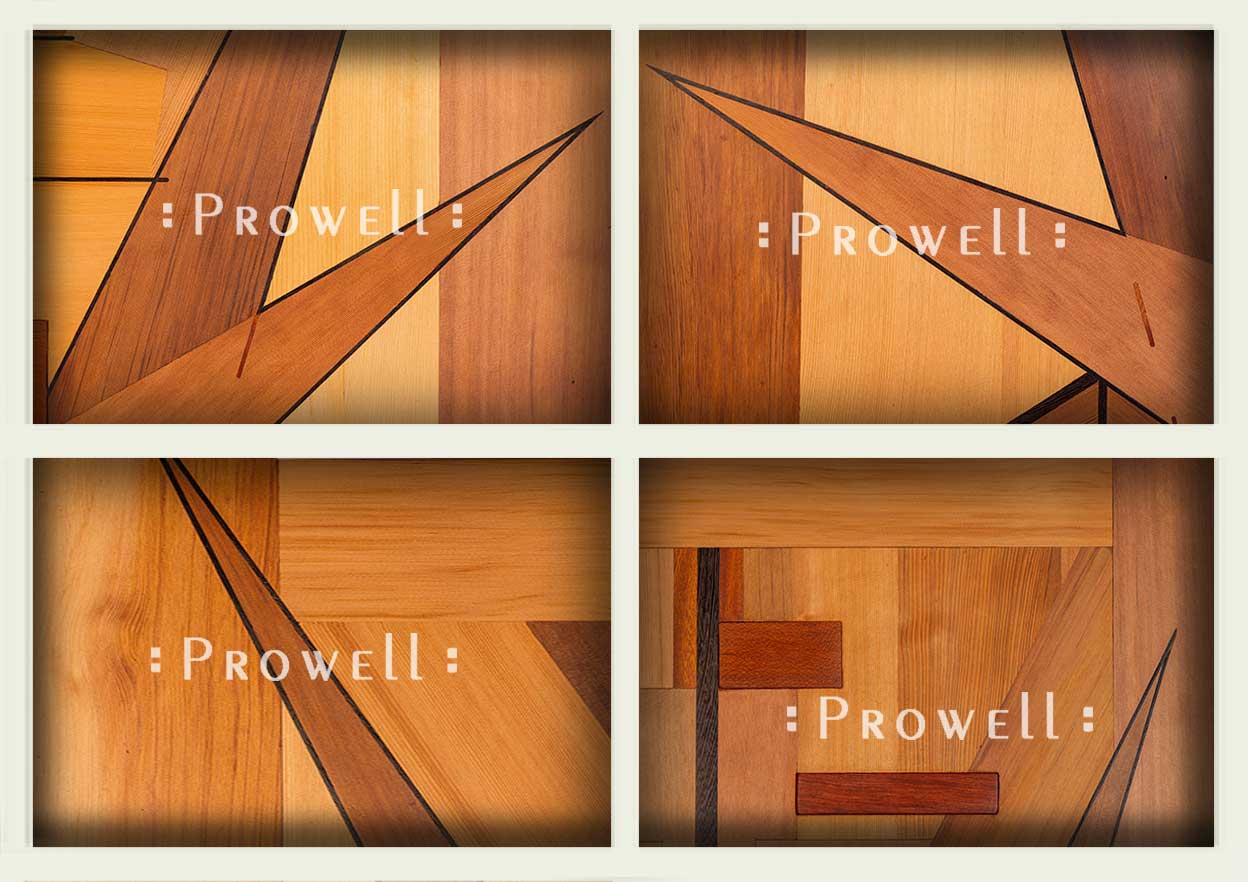

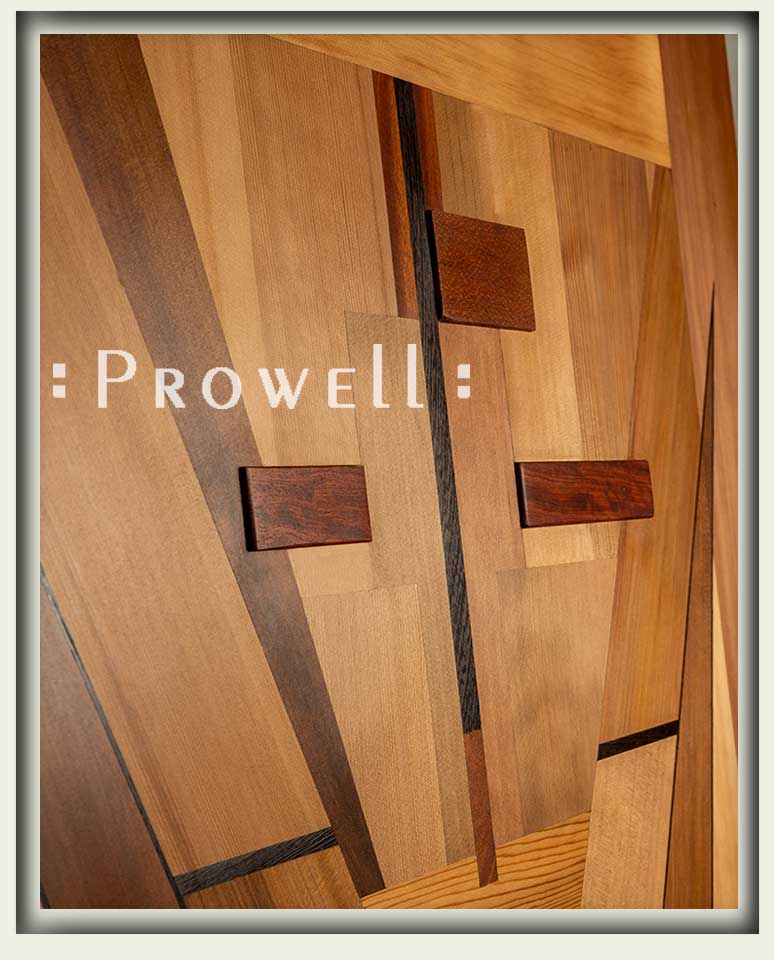

The back side of the wooden garden gate 217 is nearly identical to the front. This is not marquetry, where thin veneers are inlaid onto a solid substrate; Each piece is full thickness, cut to fit, and joined with various custom joints.

WOODEN GARDEN GATE 217

Correction: Inlays do exist throughout this gate design. What we’ll call continuation inlays–bordered by strips of African Wenge

WOOD GATES 217

Not too dissimilar from an art deco aesthetic, featuring Bubinga reliefs, seated into ½” deep mortised pockets.

PRIVACY GATES 217

Entry gate 217 features repurposed silver.

CUSTOM GATE 217

Posing.

![]()

In-Progress

BUILDING THE GARDEN WOOD GATE 217–PROGRESS

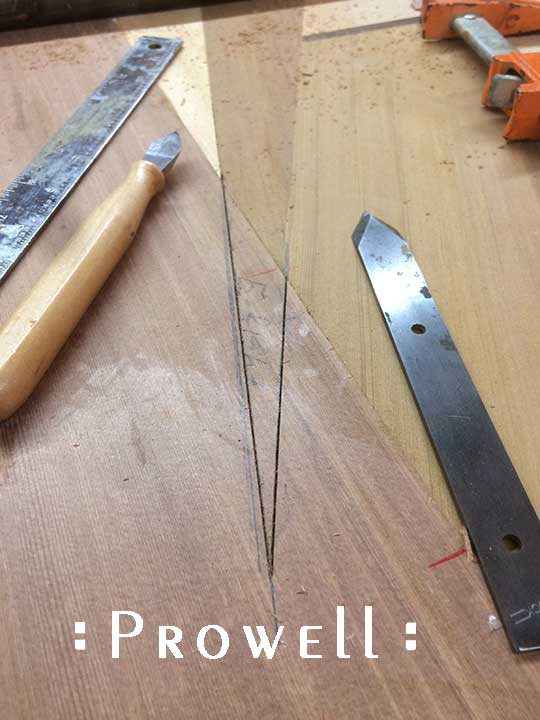

The beginning. Angles/vectors. Acute and obtuse, complicated by a subtle lack of symmetry.

In the 1930’s, Roosevelt’s New Deal included the WPA (Works Project Administration). Ultimately employing 8 million people to resurrect the infrastructure, the WPA also employed tens of thousands of artists–musicians, writers, painters, sculptors, and actors. Luminaries such as Jackson Pollock, William de Kooning, Ralph Ellison, William Faulkner, Diego Rivera, Nelson Algren, Saul Bellow, and Richard Wright, The program was for all American artists–women, African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanics . . . Although the program was often criticized for running considerably over budget and time, the purpose was not to save money, but to employ those who needed work. Eschewing production machinery and time-saving protocols in lieu of the quality of hand-hewn workmanship, and the resulting pride of the artists and craftsmen. Roosevelt was rebuilding the nation’s sense of self, project by project. Artists were paid $23.60 a week; tax-supported patrons and institutions paid only for materials.

Among the various programs and projects, there were also book binders. Designing and creating leather-bound works of everlasting quality and beauty. Prowell’s gate #217 was inspired by an amalgam of book designs cultivated from the surviving photos and rare book collections of the 1930’s.

217–PROGRESS

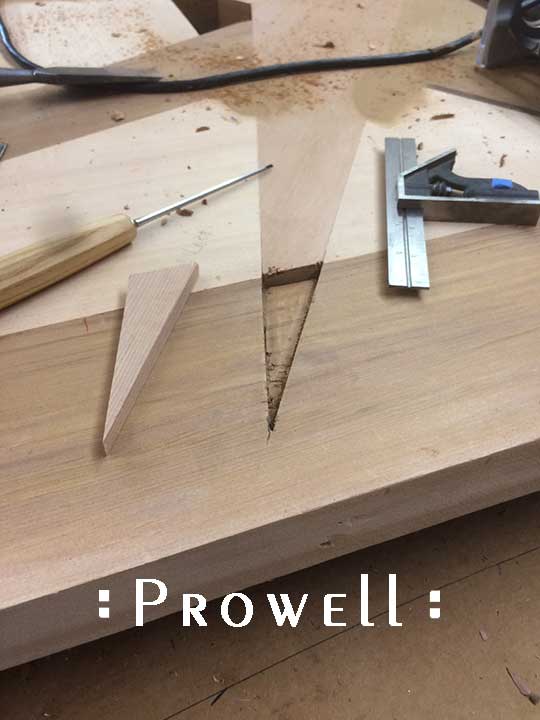

A puzzle, if anything. Pieces fitted to an unrelenting geometry of angles and joinery. One piece at a time. The pattern itself resides only in Charles’ head; no drawings exist.

217–PROGRESS

Slightly off center axis.

217–PROGRESS

217–PROGRESS

A top mast of wenge and honduras Mahogany inset into the upper section of the wood gate.

217–PROGRESS

217–PROGRESS

Aunt Mary’s family silver, passed down to a current era and culture when such heirlooms are courteously, carefully, dismissed as clutter in the cupboard.

217–PROGRESS

To ease your conscience, or Charles’, all but one platter of the wedding silver was sterling. The rest was plated. Aunt Mary turned 95 as these words were written.

217–PROGRESS

The silver was an after thought. The 217 was interrupted with an annual September trip to Pacific Beach and a visit with Aunt Mary in La Jolla.

217–PROGRESS

After some deliberation, the two lower bottom solid panels of wooden gate design 217 are revised to accommodate the silver on the feature side of the gate only. below showing the property side, with wood insert panels at the bottom left. .

217–PROGRESS

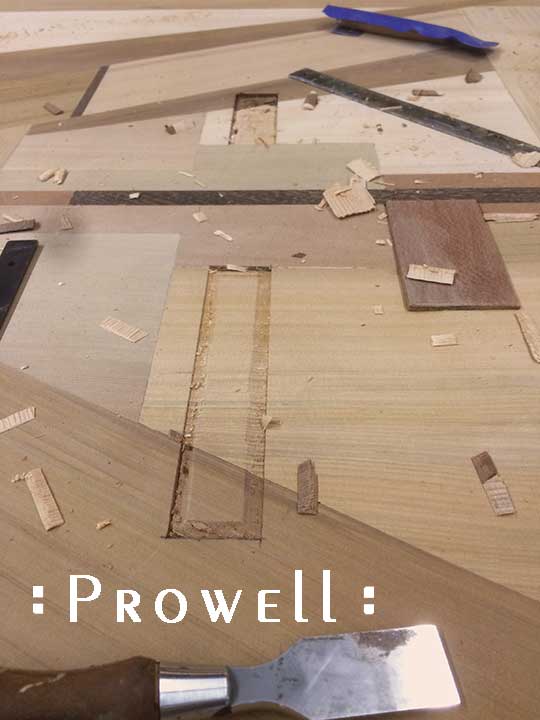

Knifing the continuation inlays for the artistic wood gate 217.

217–PROGRESS

217–PROGRESS

The continuation inlays for the garden gate 217 are scored with a marking knife then chiseled against that scored line. Working down to a depth of ¼”.

217–PROGRESS

The inlay is a remnant from the primary stock and insures a perfect match in color and grain.

217–PROGRESS

Glued and fitted in place.

217–PROGRESS

WOOD GATES 217–PROGRESS

Scoring and chiseling for a series of reliefed inlays in bubinga.

217–PROGRESS

The bubinga relief blocks, comprising the only features not on the same flat plane.

217–PROGRESS