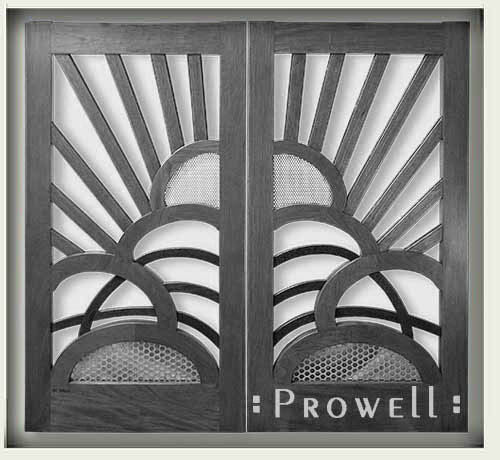

Wood garden gates 203 are perforated stainless steel, and black acrylic rod. Wenge highlights. The 203 was created as an idle pastime and ultimately finding a home in Virginia.

GARDEN GATES 203

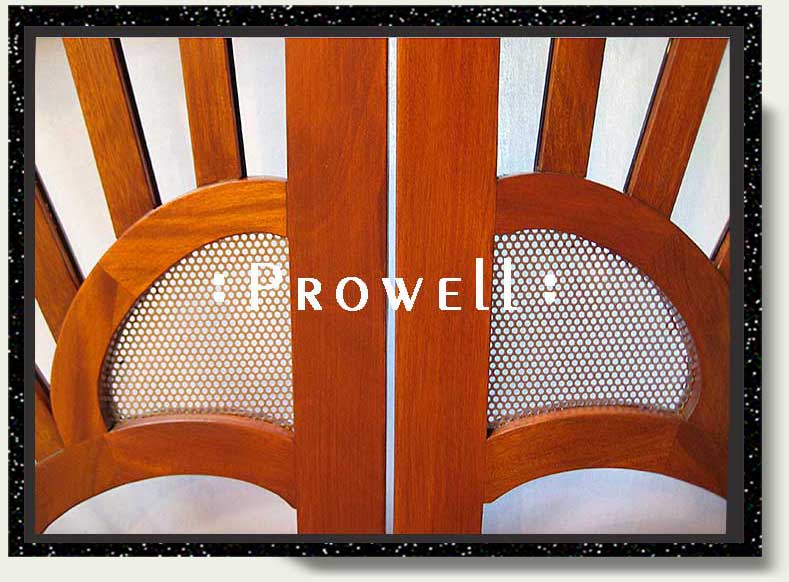

The lower inserts of the double gates 203 has perforated stainless sheets with 1/2″ diameters.

WOOD GATES 203

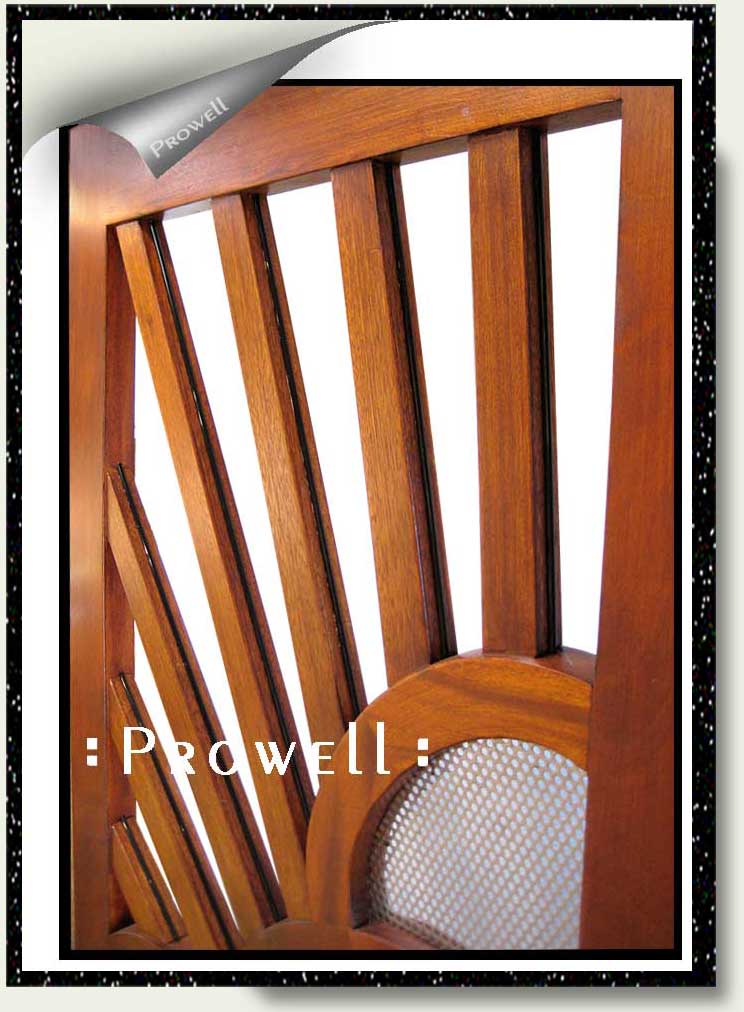

The 1/4″ dia. acrylic rods, embedded into the picket burst of the outdoor gates 203.

WOODEN GARDEN GATES 203

The upper perforated stainless insert as 1/4″ diameters.

WOOD GARDEN GATES 203

Fairfax Station, Virginia

One must assume the new wood gates themselves are only the first step in an ongoing revitalization of the landscape.

CUSTOM WOOD GATES 203

Photo credit: Ben Prowell

Photo credit: Ben Prowell

WOODEN GARDEN GATES 203

The #200 series of gate designs are not commissioned works. When finished they are summarily relegated to the walls of the shop until eventually someone makes an offer and they’re shipped off. Leaving, as shown below, a noticeable blank on the wall waiting to be filled. The garden gates 203 were meant to fill that vacancy and yet, as can happen, they were sold while still under construction.

Photo credit: Ben Prowell

Photo credit: Ben Prowell

![]()

Old House Interiors 2008

Click Here for the PDF download

Click Here for the gallery of Articles and Features

![]()

In-Progress

BUILDING WOOD GARDEN GATES 203–PROGRESS

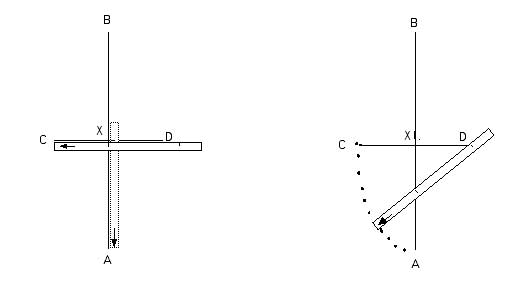

Ovals. Or ellipses. –Essentially the same, although the ellipse is a precisely defined figure in mathematics.

–In college, we learned to lay out an ellipse with a slide rule and a compass. Shortly thereafter, the shop applications involved several axis points and a stick of wood that acted as the compass. But somewhere along the line a jig was invented and the result was an oval. But even this might be considered old world in this day and age, with the gradual improvement of CNC computerized tools that follow the entered code to fabricate a true ellipse, unassisted. Woodworking techniques are subject, like everything, to changing advances.

Below, the old-school geometry of creating the ellipses for the wood gates 203.

203–PROGRESS

The first oval for the wood gates is clamped and because the weather has turned toward spring, the annual fruit flies have returned to hover in a specific area within the shop. Every year, for 28 years, they return in the spring and occupy the same airspace near the router table. A dozen or so, drawn back by kernels of genetic chromosomes that had their ancestors from the previous years telling them where to go and how to get there and what to do once they’ve arrived. Which is basically nothing. They hover. And always in the exact same spot. They arrive the way the carpenter bee returns every spring. He/she, or an annual descendant of the original he/she, surfaces from the home bored into one of the rafters and through the same passed-on genetic code, makes his/her way around the shop, settling into a hovering pattern just above the workbench and in some sort of agreement, he/she behaves like a courteous tenant.

Which has me thinking of the baby boa constrictor who lived in the thatchings of the ceiling of a house I once occupied in Paraguay. About six feet directly over my hammock. A Paraguay still infested with Nazi SS officers who patronized the same little corner cafe every morning in Asuncion, occupying the airspace with their halting rigid accents.

203–PROGRESS

The patterning and fabricating of so many ovals of varying dimensions is an absorbing undertaking. At some juncture, progressing to an increasingly smaller oval that cannot be accommodated by the jig and we must turn to a drawing that is then cut out with scissors like a grade-school project to where it can be traced onto the wood. The wood itself is then cut on the bandsaw and trued with spokeshaves and radius hand-planes.

It was interesting how the constrictor was absent during the day. I don’t know where it went, but always in the evenings and the long long nights, he found his way back above my hammock and always, extinguishing my little reading light and the slow acclimation to the darkness as I lay awake in the insufferable heat with my eyes on the ceiling until I could distinguish the thatching from the Boa’s camouflaged presence before closing my eyes. I could see the expansion and contraction of it slow breaths.

Always, every morning, I returned to the cafe a little after 6:00 a.m., relishing the daylight hours and hating the long nights and lingering over my breakfast for an hour and to the accompaniment of consonants issued from the German palettes like nails, or broken shards of glass. To listen to a language like that at six in the morning was like dragging yourself over barbed wire. Which had me wondering if Germans wrote poetry.

203–PROGRESS

Fabricating a series of ellipses.

We take our ellipses and like pieces to a unknown puzzle, arranging them in a process that is nothing if not intuitive. The instincts of a playful eye no less deliberate than the same strapper courting, even touting, those occupying the adjoining table every morning on the terrace of that cafe with the odd sensibilities of . . . a fool.

I’ve never thought to mention, to anyone, those weeks in Asunción.

It hardly ranks with the poignancy of a good cliffhanger. I was young, and blessed with the impervious nature of a brainless strapper whose only acquaintance during those weeks was a smallish boa curled into the fronds of my ceiling. I could easily have moved to new quarters, and for that matter I could just as easily have patronized a different cafe.

203–PROGRESS

One morning, one of the Germans stood from their table and approached mine, asking to borrow the salt. He spoke in English, as if to confirm an assumption that I was American. An English with the truncated phonetics of a hard geometry and I nodded, not actually answering, and for a moment he stood in place, impeccably groomed, studying me in my road-worn get-up. Waiting, I would imagine, for some response to confirm my Americanism in a city without tourists. Concerned, I would imagine, that as an American, I was in pursuit of righting certain past wrongs.

Considering countries and borders and how as a kid, you could simply cross the county border from one Illinois county to another and be beyond the jurisdiction of the local authorities. And through a network of dirt paths graded for harvesters and combines, the breach from one county to another could be managed without actually traveling on the county roads themselves. But you had to know these roads, or tractor-paths. And who else but the sons of farmers to know best, each and every field road through a network of corn and soybeans and wheat that was nothing short of a labyrinthine maze.

Paraguay has a history of German immigration dating back to the 1600’s. As does Argentina. A German leaving, say, Germany in, say, 1945, would not have been a a stranger to Paraguay’s ancestral heritage. They would have been accepted, and harbored, because of their German origins.

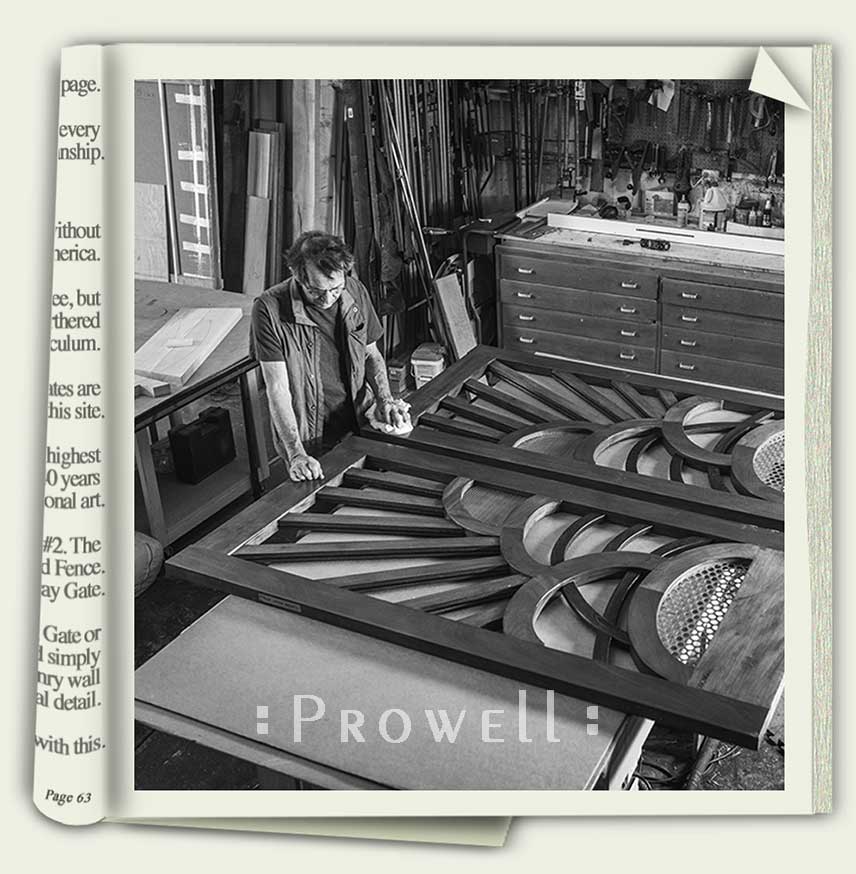

Back to building the double wooden gate design:Below, a look at the pattern of ellipses joined, clamped, and sanded into a single assembly.

203–PROGRESS

I must test the ellipse assemblies. For strength. From many angles, as if I were a boa myself.

The boa appeared so relaxed. His length intertwined in and out and over the fronds and branches like spaghetti spilling over the edges of a fork. The foreseeable danger of falling from its roost; a deep dream- – perused perhaps by a boa predator and in its sleep flinching enough to lose its balance and falling, landing like dead weight across my own sleeping face.

203–PROGRESS

Below, a look at how the patterns are coming along. Working at close range, focused on the minutia, might be compared to an impressionist painting, viewed at close range, and again, at a distance. A step ladder rests nearby in an attempt to see the converging lines as they’ll be viewed if approaching the wood gates from a distance.

Each piece is labeled, in a rather confusing index of confusing labels.

Once, following weeks in the crisp untainted air of the Andean Altiplano, I came down to arrive in a humid, fetid Guayaquil, Ecuador at two in the morning, utterly exhausted, happy to find a small concrete room off a deserted street reeking from the stench of open garbage piled along the curb. Too tired to undress, I made a customary check of the bedding, lifting the straw mattress to see a nest of cockroaches startled by the sudden exposure. Long cockroaches, in the 1″ to 2″ range. I lowered the mattress back in place and laid down and was asleep instantly and the incident is brought to mind with the same wonderment, now so many years later, that I slept for two straight weeks beneath the slinky boa as if we were pals. It’s very possible the cockroaches had their way with me through that night in Guayaquil, but if so, I nevertheless awakened that next morning unscathed and unbitten and for a few hours man and beast shared one another’s presence like, well . . . like pals.

203–PROGRESS

Several sheets of .0565 gauge perforated stainless steel, and I see the finish line. How close, actually, we are to finishing these unusual garden gates.

Below, the wenge arches re-designed and the perforated stainless fitted into place. The right side of the our wooden gate design is assembled and glued and clamped. The left side and top rail will be removed to allow the insertion of the sunburst pickets. A five-hour day that passes like 20 minutes.

The cockroaches, although the size of my thumb, were essentially harmless and unless I slept with my mouth open, I would awake undisturbed and unharmed. The boa, about the diameter of my forearm, was too small and had showed no interest in me as a meal. The old Germans, whether in exile from war crimes of long ago, or not, were far removed from whatever parameters may have once sent them to Paraguay.

203–PROGRESS

With both gates assembled and finished, we now turn to the last step. Installing the 1/4″ dia. black acrylic rods along the sunburst pickets. One at a time, using an epoxy/acrylic quick-set glue, they’re fitted and clamped.

May 1st, suddenly. I pay so little attention to days of the week that a calendar is of almost no use, as one has to know which week within any given month lest the dates themselves are rendered pointless. Thinking of May Day and how as kids on our farm in Illinois, my middle sister and I would ride our horse to the neighbor’s farms, bearing fresh flowers from our house garden. A tradition, of sorts, that had one of us dismounting to tip toe up to the front porch, leave the flowers, ring the bell, and run back to mount Promise, our horse, and then ride like the wind to escape across the north field and through the freshly plowed furrows of earth so black and rich it was, well . . . aromatic. Of course the neighbors knew it was us, watching from their porches as we disappeared off the rise, laughing our heads off.

203–PROGRESS

Thinking of Asunción–the old Germans, and, well . . . the boa. How if I were to have invited someone to my room–which I did–and mentioned the boa and it’s overhead alignment to my bed–which I didn’t–you have to assume the reaction would be memorable. Move the bed. Kill the boa. Resolve the situation some way or another. To my guest, the boa would be considered a clear and present danger, and to remain within the grasp of such danger was a product of either lethargy or what we might call the ostrich syndrome–pretending the danger didn’t exist. An acquiescence recorded now and again over the course of history where the populace gives over the logic of their own intellectual bearing to the rising, convincing presence of a despot.

But the Germans, who in my daily visits to the cafe in 1976, were easily old enough to have been instrumental in a much larger context of danger, and the pretended absence of danger.

It is now a matter of public record, through the Freedom of Information Act, just how many reputable reports were arriving at FDR’s desk regarding the genocide. As early at the fall of 1939. A phenomenon even more lucid to the German citizenry. The Aryans, who had no issues with their Jewish neighbors and friends, and yet because they were in the thick of it–because they were sleeping beneath the boa, they failed to act. Or react.

But it’s more. As early as January of 1918, Eleanor Roosevelt writes to her mother-in-law regarding a party she and Franklin were invited to. She writes: “. . . I’ve got to go to the Harris party which I’d rather be hung than be seen at. Mostly Jews.”

Does this help explain why the reports flooding FDR’s desk, as President, were categorically ignored? Why he repeatedly refused to repeal the immigration laws to allow German, Polish, Belgian, and Austrian Jewish refugees to immigrate to America? Why a boatload of them were left stranded off the NY harbor for two months in 1941?

Eleanor’s social circles expanded during her years in the White House, beyond the tight blue-blooded structure of the bevy of Roosevelt cousins and kin that formerly dictated her opinions. She became a champion of various causes, such as women’s rights and even human rights. She in turn swayed Franklin’s perspective and although they were slow, as the First Couple, to react to the genocide in Europe, they did react. And against Churchill’s wishes, the plan for a D-Day landing and full-on assault at the German core was set in place.

There are more letters-of-record from the pen of Churchill regarding his established antisemitism than seems so implausible from a statesmen occupying a world stage.

In October of 1941, in the thick of it, the news from within the belly of the beast, by way of innumerable personal letters, was as widely known and acknowledged as the starving affects of Churchill’s blockade. Walter Mater, an SS police secretary from Vienna writes to his wife on the day following a massacre of Jews in Mogilev. ” . . . My hand was shaking lightly”, he wrote, when he shot the first truckload, but by the tenth he was aiming more calmly. He had ” . . .shot securely many men, women, children, and infants”.

Round about 1944, there was a mass exodus of SS officers escaping to South America. To Paraguay. Why Paraguay? Well, they arrived with large, very large amounts of plundered money, at the doorsteps of a country that had almost no awareness of the world stage, much less the nuances of war crimes. Paraguay, in 1944. No TV. No internet. Very few radios, concerned mostly with a local love for dramatic soap operas. A single newspaper, but no network of AP or UPI links. They arrived with a veritable fortune, sacked from millions of massacred Jews, to settle into a pleasant existence of fellow countrymen, most of them in their mid-twenties, safe from the world tribunals that wouldn’t get geared up for many many years to come.

In 1976, just 32 years later, as men in their mid-fifties, they were enjoying a renaissance of power, impervious to anything. Unrepentant, emboldened even. Chile, just a few miles off, was under the hand of Pinochet. Argentina, a few miles in the other direction, was in the thick of the ‘Dirty War’. Their tactics of mass massacres were uncomfortably familiar. Both countries were blacked out from world news. No news from the Northern Hemisphere reached the citizens. No news was released to the world. The atrocities went on for many many years, unbeknownst to a world beyond the borders of these cultures, and yet fully known by the constituents, the citizens, terrorized into the Ostrich Syndrome of sleeping beneath a boa. The clear and present danger of such acquiescence.

Being in Asunción, and Chile and Argentina at this time, beyond the borders recommended by the American Consul, to travel alone in a world suddenly without travelers, was to be engaged in endless whispering conversations with local citizens wondering when the world was coming to their rescue. Where was America? They asked me. What was the news of their plight in America? But of course the American populace was no more aware of their plight than they were of the situation in Germany 1939. It would be another 8 years before news of Argentina’s Dirty War arrived in the States. Small articles, leaking out from page six of the Times and read by me with the impact of being slapped hard on the face.

As a parting note, for so long there has, among the gate galleries, been a particular gate style originally designed for the novelist Isabel Allende. Someone with the good fortune to have escaped the atrocities of Chile under Pinochet. I had met her once, chatting on a bench in Oliver’s Books in San Anselmo about books and favorite bookshops and although I had wanted to mention Chile, my time there during Pinochet’s rule, a year after her departure to the states, the subject obviously never came up. Instead we passed an hour chit-chatting about nothing of any real importance. Books and bookshops.

Meanwhile, clamping the black acrylic rod to the spokeshave pickets.