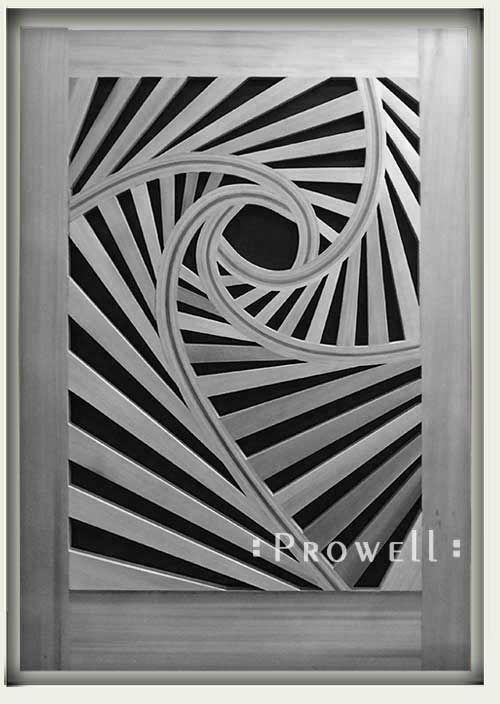

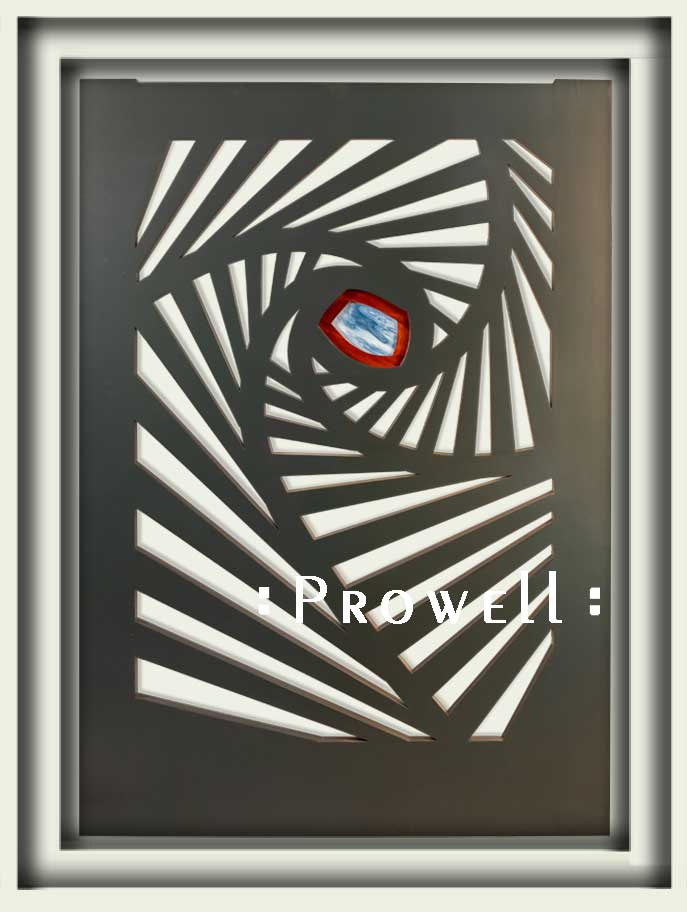

The spiraling wood gate design 215. A pinwheel caught in a windstorm.

WOODEN GATE DESIGN 215

The pinwheel gate pattern with each segment spiraling toward a focal point of stained glass with a bubinga frame.

Although the original wood gate 215 was unfinished, it appeared a bit too confusing to the eye. Consequently a painted finish.

WOOD GATE DESIGN 215

Given the varying tones of unfinished cedar, and how that only further complicated the pinwheel gate design, a painted finish seemed the best option.

![]()

In-Progress

BUILDING GARDEN GATE 215–PROGRESS

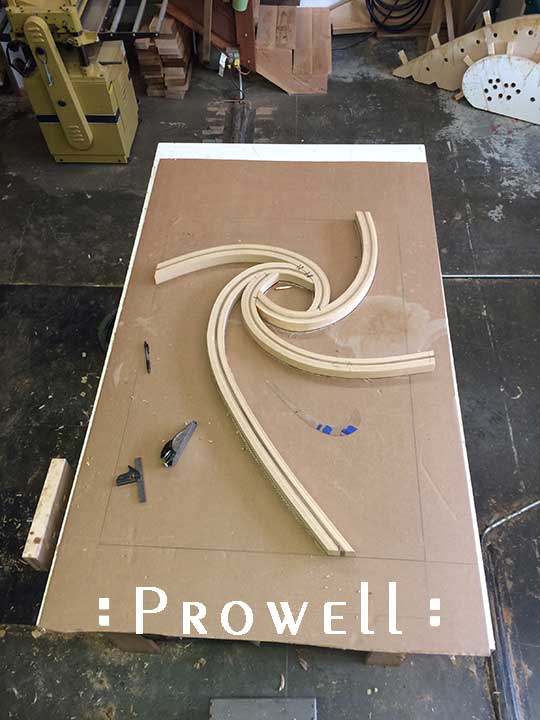

The bent lamination–the spine of the vanishing perspective–is created on a clamping form, 19 strips at 3/32″ thickness.

215–PROGRESS

The drum sander insures each strip is the same thickness. A trial and error process until we come to a thickness that doesn’t break when clamped to the form.

215–PROGRESS

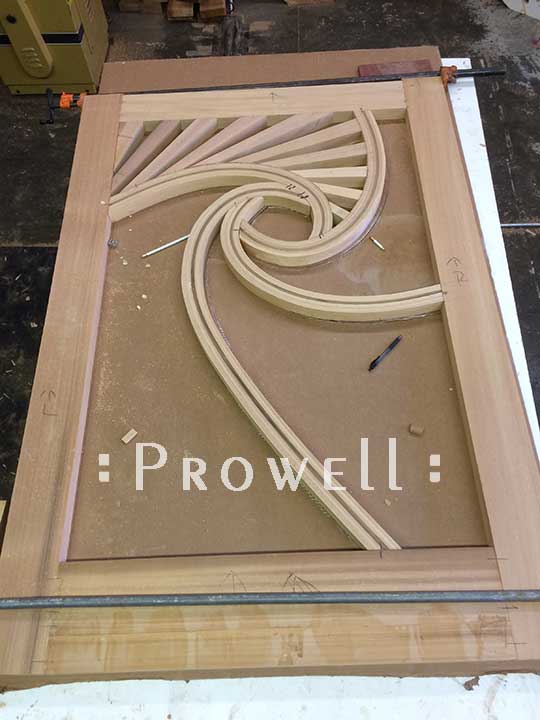

Eventually the pinwheels of the spirograph gate design are finished and a layout is arrived at by fiddling and fussing toward what feels right. And marked in chalk. Once again, as with so many designs, fabricate the primary pieces to the puzzle and then set about finding their most advantageous placement.

A temporary 1x frame is used for this purpose.

GARDEN GATE 215–PROGRESS

The first two spines in place.

215–PROGRESS

215–PROGRESS

Once the primary spines are cut and dry-fitted, we can proceed with the first section that defines the pinwheel gate design.

215–PROGRESS

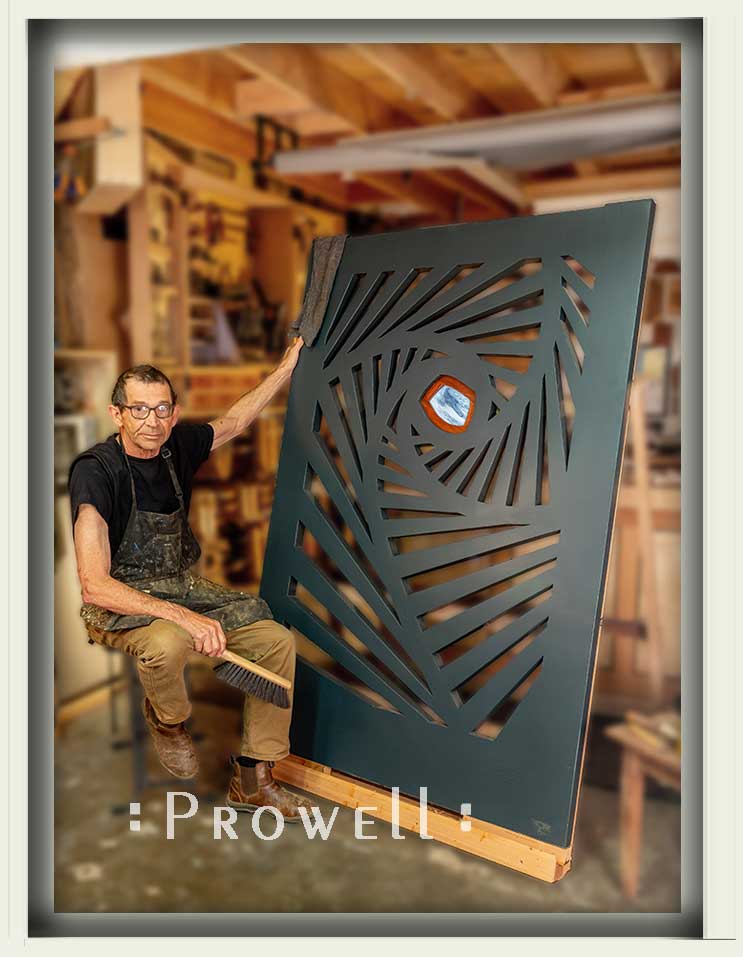

Two sections joined and glued and too late now to change your mind. The longer bent lamination, or spine, extending down to Charles’ feet, remains loose, enabling whatever joinery will be required. Meanwhile, a pause for perspective, and the first impression of this vanishing perspective wood gate begins to take shape.

215–PROGRESS

The crucial decisions at this juncture pivots on the sequence of glue-ups. How to mortise the joints and ultimately fit those joints without disturbing the placement of the primary bent spine by so much as a millimeter, lest all the succeeding joints be impacted as if nudged like a row of dominoes.

215–PROGRESS

Athousand years from now, preservationists uncover from the attic of a Midwestern farmhouse the only known portrait of Prowell in his prime. An unjust comeuppance, they conclude. In overcoming an unsightly deformity, the artist adopts the reclusive focus that fosters the boundless gifts that blossoms over those infamous decades a thousand years past into that enviable disallowance of distractions.

Being humans, the drooling preservationists site the riches and rewards of a Tutankhamen’s Tomb traveling show. They return to the farmhouse, still inhabited by Prowells of the 32nd century. A mountainous bounty of artifacts stacked to the ceiling, pressed against the ancient girders and groaning joists such that the only sensible approach was snow shovels. Occupying that attic, moving in basically with bedrolls and camp stoves against the debating concerns and insouciant doubts of the surviving Prowells. Every paper, every sketch, every text, every correspondence deliriously translated into the imagined riches of beach houses and yachts and wealth compounded against the team’s meager curator salaries.

The chance of a lifetime, they whisper amongst themselves. Snickering whispers, raised eyebrows, clearing the last remnants with sore backs stooped from sleeping on bedrolls and somewhat emaciated cheeks from camp stove meals tasting of propane, they crowd into the single cab of a rented driver-less cargo truck, sitting on one another’s laps laughing and joking with foolish optimism and unwarranted arrogance while the truck, with no one at the helm, navigated by chips and satellites, travels in circles up and down the confounding back roads of southern Illinois, paved roads becoming semi-paved roads becoming gravel roads morphing into dirt roads with the clear and present danger of no way out.

Abandoning the truck at Karber’s Ridge, with its ridge-top vista exposing the endless canopy of an unknown world, they strap what they can manage on their backs and trek into the ancient Moinweenga footpaths choked with mulberries big as cantaloupes and cottonmouths thick as trees and an entomologists trove of buggery feeding on the trekker’s soft pink cheeks and gradually the papers, the archives, the burden of backpacks litter the forest floor as the trekkers succumb to hallucinatory panic. Giant albinos, eight foot tall if anything, lurking in the leafage.

Meanwhile, back at the farmhouse, the Prowell descendants are thrilled to have their aforementioned attic cleared and swept clean, free of charge. A millennium of trash giving way to the revitalization of a rec room with an old fashioned billiards table and a dart board and a checkers table and a working moth-eaten couch set to the southern dormer overlooking the lower pasture where once, so awfully long ago, the native Moinweengan women lay naked bathed in the light of a full moon, face down in a burrowing pelvic gesture against the nutrients of such rich black topsoil so fertile to foster the immaculate conception of newborn Moinweengan babies fed on like ripe cherries, as legend goes, by giant albinos lurking in the riverbed.

WOOD GATE 215–PROGRESS

Fitting the bubinga frame into the center focal point of the spirograph garden gate 215

215–PROGRESS

The stained glass in place.

215–PROGRESS

If you’re a parent, or a grandparent, and you haven’t already introduced the munchkins to the world of spirographs, do so immediately.

More on spirographs, Click Here.