![]()

WOOD TALK

A discussion of Wood Species and their suitable properties for joined, exterior assemblies.

There are four requirements for ‘joined’ exterior assemblies. By “Joined’ we do not refer to such methodologies as stacked assemblies, where layers are mounted onto layers and secured with screws or nails or bolts. We are referring to assemblies that are secured by the sequence and complexities of their joinery, such as the Shinto shrine in Ise, Japan, which was built in the 3rd century and stands in pristine condition today! Or the Horyuji temple, built in 607A.D. in Kyoto and standing today! Or a wood stave church near Oslo, Norway, built in the 13th century. These, and other examples, have survived because, for one, they have employed a system of joints that allow the wood to grow, shrink, age, and season as befits itself. But also because these structures are beyond the reach of tourists which can account for so much of the bacteria damage to aging wood structures, as well as the conditions that have seen the wood in a stable environment with regards to moisture and dryness. For instance, boat-builders in New England soak their preferred stock in the salt water of the local bay for 30-40 years. Were they to remove these logs from the conditions of total submersion and onto the dry dock exposed to the heat and sun, the wood would undergo severe trauma in a confusing effort to navigate from total moisture content to nothing more than the humidity in the air. So consistency is important, whether dry or submersed. With these conditions, and the wood itself–i.e the right wood–an assembly will last a very very long time.

- The appropriate Rot-resistent Woods (Specific species and milling grades: Quartersawn, etc).

- Stable grain patterns (Mature harvests with tight growth rings).

- A moisture content of no more than 7-9%.

- Renewable Harvest.

![]()

Wood Talk

1) WOOD SPECIES

A discussion of their suitable properties for joined, exterior assemblies.

Rot-resistent Chromosomes Matter

What species of wood is actually best suited for the lasting integrity of an exterior assembly? There are only a handful of woods with the inherent properties that are genetically rot-resistant to exterior elements. By genetically resistant, we mean the inherent means of defense against the debilitating infestation of insects and bacteria. Trees, like animals, vary in this regard. A forest deer has few defensive tactics and might be considered as fodder for the animal higher on the food chain, such as the bob cat. The coastal redwood, living to several thousand years, is practically indestructible, given its impenetrable fire-resistant bark and peculiar repellent tannin, to where it’s only real enemy is the chain saw.

We will not take into account a bevy of wood species drawn from the rain forests in a process closer to annihilation than sustainable foresting. Nor Larch, Spruce, Cypress, or even Sugar Pine, all of which exhibit certain properties conducive to withstanding the elements but not all the properties, such as their dimensional stability and their work ability to joining and mill work. If we were concerned with only a wood’s gift for withstanding harsh conditions, then Larch alone is worthy of a ransom’s prize: For the pilers that have held up much of Venice, Italy for the past 600 years, or the millions of board feet as railroad cross-ties and the engineering marvels of all those magnificent trestles..

When we look to suitable wood species for exterior joinery, we must go beyond its mere resistance to the elements and consider:

- It’s dimensional stability (Is the trunk straight and branch-less and with good girth? )

- Is it dimensionally stable? ( i.e.does it expand and contract excessively? )

- Is it workable, as in can it be milled and shaped without splitting and checking and burning the cutting edges?

Teak, Cedar, Redwood, Mahogany, and Oak

Teak, Cedar, and Redwood are nearly identical in their high resistance to decay. Mahogany and Oak are less resistant and require regularly maintained finishing seals but are both common in boat building and outdoor furniture because of their density. (All of the above, by the way, will weather and gray out to an identical gray if either left unfinished or applied with a clear seal, but Mahogany and Oak will eventually become vulnerable to bacteria without a regularly maintained sealing finish). Teak, Mahogany, and Oak possess a higher density, which means the fiber between the rings is closer to muscle tissue than fatty tissue. This results is heavier assemblies in the field, if that is a criteria, but it does not result in an assembly with a longer life span.

Teak:Plantation teak is largely harvested in Indonesia, but also in Central America. Myanmar teak (formerly Burmese teak)) is theoretically prohibited because of its poor harvesting techniques, and yet is widely available through imports via China. It is important to insure teak purchases are certified, and to verify the certification. When advertised as ‘cheap teak’, you can be assured it is being illegally harvested in Myanmar and sold via black market through China. Teak has excellent inherent tannins, or oils, resisting bacteria and fungus. Figured grain.

**Extremely workable wood.

**Retail Cost: approximately $30/per board foot.

Redwood: Grown exclusively along a 200-mile stretch of northern California coastline. Because this industry is so tightly regulated, the former logging giants of Humboldt and Mendocino counties are littered with abandoned mills. It is currently being harvested on a short cycle, producing sustainable results that are, unfortunately, without the properties inherent in old growth harvests. Redwood has a high concentration of tannins, like teak and western cedar, that thwart the propagation of bacteria (rot). These tannins require a growth cycle to mature into their full genetic strength and are consequently absent in the present-day redwood harvests. Due to the abnormally large diameter of the trunk, the ‘heart grain’, located near the center, and oldest part of the tree, is tight and stable. But ‘old growth’ redwood is available only as a special “Forest Floor” permit or as a recycled product, drawn largely from a series of former military bases in California that were built with old growth redwood and were all closed in the 90’s. The current ‘short-cycle’ redwood has a fibrosity in its grain that is far far more porous than old growth, and therefore, far less stable or visually pleasing.

**Retail Cost: Approximately $7/per board ft. for kiln-dried clear all-heart. (In northern California. Far far more elsewhere)

*NOTE: We interrupt here because it is worth noting that the tannin oils mentioned above as the identifiable properties of both Teak and Redwood are also the potential menace. Glue, as in the woodworker’s glue, must have a porous surface to grip or adhere to. Because these tannin oils emanate from the tree’s fiber to coat the surface, any glue applied will simply sit on the skin and fail to create the sort of bond required. Almost immediately after both redwood and teak are milled or a joint is cut, the oils begin rising to the surface to prevent a glue-bond. The answer? Assuming one mills all their components and then turns to gluing and assembling, the technique involves a light hand-sanding off the new thin layer of oils that have risen since the milling, and then without delay, apply the glue and clamp the joint air-tight, all before the oils rise to coat the face of even the most freshly milled surface.

Mahogany: There are many species of mahogany–usually denoted by the country of origin, but not always. Santos, Sapele, African, Fiddle-back, Philippine, Honduras, and Cuban. They are all exotic and endangered and yet with proper research, available as sustainable with the exception of Cuban. The mahogany industry has been over harvested. If a sustainable source can be found, look for full figuring and a deep reddish brown coloring. Mahogany, although a good species for resisting the elements, does not posses the same ideal characteristics as teak, cedar, and redwood. It will shows signs of wear if not maintained.

Retail Cost: Approximately $7/per board

Oak: There are approximately 600 species of oak with the most common being red and white oak. White oak being the one wood species with a resistance to rot and decay and commonly used in boat building and outdoor furniture. Generally good strength and hardness and resistant to insect and fungi due to a high tannin content. The strongest and most stable white oaks are quarter-sawn. What is quarter-sawn? Quarter-sawing gets its name from the fact that the log is first cut lengthwise into quarters–wedges, essentially, with a right angle ending at approximately the center of the original. Each quarter is cut separately by tipping it up on its point and sawing boards successively along the axis. That results in boards with the annual rings mostly perpendicular to the faces. Quarter sawing yields boards with straight striped grain lines, greater stability than flat-sawn wood, and a distinctive ray and fleck figure.

Retail Cost: Approximately $3-5/per board ft.

Quarter-sawn: $7/Bd Ft. Retail.

CEDARS

Western Red: The more common cedar found in exterior constructions. Harvested in British Columbia, Canada where it is regulated with a 100% sustainability. Dimensionally stable with tight growth rings. One of the signature properties is the light and dark coloring, often within a single board. Excellent resistance to insect and fungi.

Retail Cost: Approximately $6-$7/per board foot in the west and $8-$12 in the east.

Alaskan or Yellow Cedar: A slow growing wood species with many of the trees in North America between 700-1200 years old. Excellent rot resistance. Harvested between southern Alaska and southern Oregon. Because of it’s slow growth pattern, Alaskan Cedar is rare, and when it is harvested, it normally suffers the same fate and today’s redwoods–harvested so early that the maturity of the growth rings and genetic oils are short-changed. Dimensionally unstable.

Port Oxford: Grown and harvested and milled in small, select locations in the Pacific Northwest. Fully matured harvests can be difficult or even impossible to find. A creamy white hue, aging to a stately silvery gray. Smooth with no raised grain. Due to the pale nature of its coloring, it gives unlimited options when staining. (Redwood, teak, western cedar, and mahogany are dark and cannot take lighter stain pigments) A unique, strong ginger-like scent, due to the volatile tannin oils. Denser than other cedars. Dimensionally unstable, which means that because of the early harvests, there is far more fiber between the growth rings, giving way to a vulnerability for checking and cracking as it dries. Excellent resistance to insect and fungi infestation. Although in some areas, the lower grade of Port Oxford is available as a green, knotty product sold as decking, the clear, double-kiln-dried grade remains largely unavailable to the retail public. This is the wood Charles and others used in the 1970’s in San Francisco—until it was all gone. A grove was planted in 1978, and although they are harvesting, as mentioned above, it is a premature harvest falling far short of the old-growth properties.

Why doesn’t Prowell provide fence and gate posts?

- Because we do not stock posts and are therefore subject to a similar over-the-counter cost as your local installer through his own preferred lumber yard. Maintaining an inventory of this would require, on the one hand, a sizable investment at the mill, but more importantly the need for an insulated, temperature-controlled storage facility. Because such posts can be ordered from any quality lumber yard in the country, it seems best that we leave this to the contractor on site.

- If we did stock posts– in 6×6 and 4×4–there would be an added cost of crating and shipping to the site, resulting in a post per-foot cost that far exceeded what your installer would pay locally. Western Cedar is the most commonly used post preference. East of the Mississippi, this is a special order item and you should allow two weeks. For their Prowell fence-lines, the vast majority of patrons opt for an STK grade. This is a tight knotted grade. For gate posts, the preference is often the clear grade. A full discussion of post options, including the recommended technique for setting your posts is at the following link: <https://prowellwoodworks.com/gate/postholes.htm>

Pressure Treating

- A common means of circumventing the expense of teak or affordable access to redwood and cedar to those in the east is the process of treating more affordable woods such as Douglas Fir with a chemical that resist or thwarts bacteria infestation. For the longest time, this was best accomplished with a thick coating of creosote, which might be most recognizable in connection with the railroad ties. When creosote was outlawed in the mid-1980’s, the method of pressure treating was adopted. Injected by a series of punctures pressured by a vacuum press to a depth of about 1/4″ from the surface, an arsenic-based tonic allowed the use of fir and pine and all sorts of affordable species to be used in the construction of decks and fence posts and anything deemed susceptible to rot.

Still commonly used today as a cost saving measure, a number of problems are worth noting.

- Pressure-treated preservatives do in fact transfer to the touch, as well as drain down into the water table. California recently, finally, prohibited such products from all publicly accessed areas. They should be prohibited everywhere and from all uses.

- When cut, the fiber is exposed where the arsenic has not penetrated, thus requiring the direct application of a medley of products to coat the raw grain. These are far far more transferable than the pressure-treating process, and a good deal more toxic.

- The cost savings of pressure-treating may allow one to actually afford a deck, but entertaining on that deck, above the wafting odors of poison that permeate the structural underlay, will make for a far greater problem over time.

And yet it is not uncommon for those sites east of the Mississippi to opt for this solution. We are not stewards of the earth. We are woodworkers, and will not preach a high-minded sermon to those who prefer pressure-treated posts.

Requests:

“We’d like our Prowell product in Ipe, please”

————— Ipe continues to be largely non-certified and culled from the rain forest without restraint. It is also extremely dense and heavy and a strain on normal mortise and tenon joints, as a gate is suspended against gravity.

“We’d like our Prowell product in Teak, please”

————— Although we have honored these requests in the past and will continue to do so, it should be noted that certified Teak is approximately $30 per board foot, while requiring not only the additional mill work of any hardwood, but on average, due to random lengths and widths, a waste factor of about 40%.

“We’d like our Prowell product in Mahogany, please”

————– An affordable option, and harvested with acceptable standards in certain areas. A rich amber coloring and fine figured grain and working properties. The same milling and waste conditions for hardwoods apply here as with teak. It should also be noted that Mahogany requires a finish and does not have the same resistant properties equal to cedar and teak.

“We’d like our Prowell product in Redwood, please”

—————There are sound reasons for demurring on all requests for redwood. Enough reasons to fill a book. But reading books appears to be a lost pastime. Writing books of this nature is left to pundits and alarmists and the nay-sayers who are the watchdogs and activists who are heard only by those who actually read books.

PROPERTIES

WESTERN CEDAR

Other common names: red cedar, cypress, Oregon cedar, giant cedar. Known for its extremely fine and even grain, its flexibility and strength in proportion to its weight, Western Red Cedar is a species of wood whose lumber can be used in a variety of ways. Western Red Cedar is renowned for its high impermeability to liquids and its natural phenol preservatives, which make it ideally suited for exterior use and interior use where humidity is high.

The cellular composition of cedar, millions of tiny air-filled cells per cubic inch, provides a high degree of thermal insulation, approx. 1 R/inch. Old Growth Western Red Cedars’ slow growth, dense fiber and natural oily extractions are responsible for its rot-resistant properties and its rich coloring, which ranges from a light milky straw color in the sapwood to a vanilla-chocolate in the heartwood. Second growth is different. It is a stable wood that seasons easily and quickly, with a very low shrinkage factor. It is free of pitch and has excellent finishing qualities.

- Density: 20 lbs per cubic foot.

- Decay: High resistance

- Availability: Adequate

- Color: Red brown

- Carving: Average to Difficult

- Contrast between growth rings: even

- Grain: Vertical

- Odor: Distinct aromatic scent

- Mortising: Good

- Movement after drying: Low

- Painting: Good

- Staining: Good

- Sawing: Low resistance

- Stiffness: Low

- Marine applications: Yes

- Location: Pacific NW and British Columbia, Canada

![]()

Wood Talk

2) STABLE GRAIN PATTERNS

Learning to Read Grain Patterns and Growth Rings

1A)

Illustrating three pieces of Port Orford cedar. The top board shows a Bulls-Eye endgrain, milled from the tree’s core and, for our purposes, as worthless as firewood. The lower example is slightly more promising, but in all likelihood will develop a cupping, as well as open checks down the face—you can already witness the checking. The stability of both planks is beyond acceptable levels. The bottom board is an example of good grain patterns and yet with growth rings at only 4-5 per inch, it represents premature harvesting akin to baby-snatching. Between each ring is fiber, or what we might refer to as fatty tissue. Useless and unstable and a sponge for moisture, creating a plank that will expand and contract at an unstable rate.

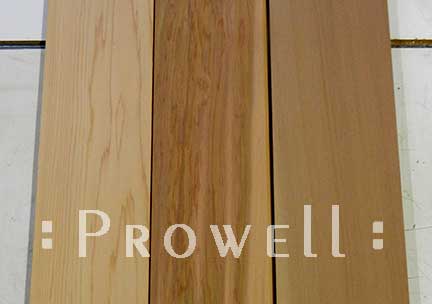

1B)

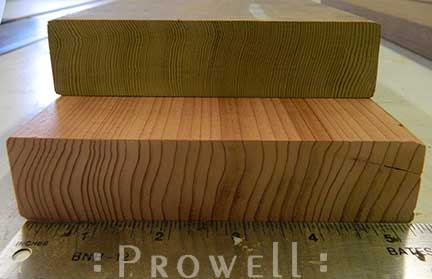

The top board is what Prowell Woodworks specs from the mill in Western Cedar, showing a mature 32+_ growth rings per inch. Even if exposed to the southern Florida or Hawaiian humidity, there will be minimal misbehavior or dimensional change. (An ideal grain pattern is as close to 90-degrees off the face of the plank as possible, reminiscent of a quarter-sawn plank.) The bottom board is a piece of kiln-dried redwood bought at the local independent lumber yard, illustrating a very young and porous tree, of about 6 rings per inch. Harvested long before the signature redwood tanning of old have been allowed to mature as a defense against bacteria.

1C)

A 4×4 clear green redwood post from the local yard with both bulls-eye grains patterns coupled incredulously with only 2-½ growth rings per inch. Understand that if you rely on this grade, your post immediately becomes the weakest link in the lifeline of what you’ve been paid to build. Don’t expect a disclaimer from the lumber yard or a homeowner quick-witted enough to understand the minutia of a growth ring.

1D)

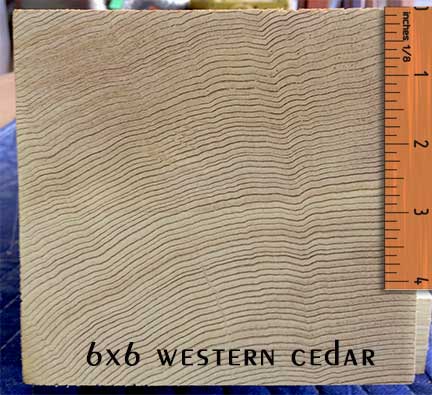

A 6×6 western cedar post, fully matured before harvest with growth rings at approximately 1/16th to 1/32nds apart. A world of difference in not only the lifespan, but the behavioral properties of a stable fiber.

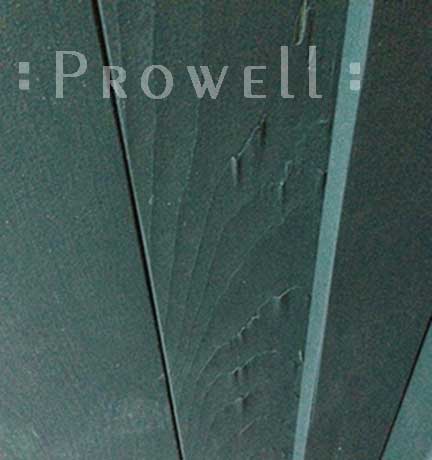

1E)

An example of a scaling cathedral plank finished with a solid-body stain prior to being shipped from the temperate climate of California’s Sonoma County to the humidity of Washington DC in August. The cedar experiences trauma and for several weeks, once installed and fully exposed, undergoes a level of pronounced dimensional change as it gradually acclimates. To apply any layered or non-absorbing finish—such as 2-part sealer finishes or solid-body stains or paint— prior to this completed acclimation is to witness an inflexible finish unable to keep pace with the dimensional moods of the wood. If the product was shipped and installed and exposed to the climate of, say, Washington state, Oregon, even California’s Sonoma County, the dimensional acclimation would be minimal; the planks have not ventured far from their ancestral climate of British Columbia. Something like, as a young adult, setting up house in the same neighborhood where you were born and raised.

1F)

Three lengths of clear, kiln-dried, western cedar. On the left an example of cathedral grain pattern, which when exposed to the shifting elements can lift, or scale away from the face. Particularly if oriented upward to collect moisture. In the center a moderate example of the same grain pattern with little risk of scaling. On the right, the ideal vertical-grain pattern that eliminates cathedral scaling all together.

Wood Talk

3) MOISTURE CONTENT

Air-Drying vs Kiln Drying

When wood is used as a construction material, whether as a structural support in a building or in woodworking objects, it will absorb or evaporate moisture until it is in equilibrium with its surroundings. The equilibration process (usually drying) causes unequal shrinkage in the wood, and can cause damage to the wood if the process occurs too rapidly. The process of equilibration needs to be controlled in order to prevent damage to the wood.

If the wood moisture content is high during the point of construction, a joint will appear tight. It will remain tight as long as the moisture content in the wood remains unchanged. But once the drying process begins, such as exposure to the dryer air and seasons, the wood will lose it’s moisture and its dimensional point will shrink, thus translating this tight joint into an unsightly gap. Although the principles are the same for interior furnishings, they are exasperated dramatically with joinery that is fully exposed to the conditions and elements outdoors.

So . . . working with dry wood in the shop is absolutely essential if the methods of construction are those of joined members and not the stacked, or layered, members of a typical carpenter’s assembly. And because of the relative importance of this feature, we are consequently overly concerned with the method of just how that wood goes from the green live fiber of a tree to the dry, stable fiber suitable for joinery.

Most all dried lumber sold across the counter in America is kiln-dried. A quick reliable process that allows the turnover of inventory. But the process itself is not dissimilar to a microwave. The quick time-line can result in ‘drying stresses’ such as checks and cracks and a loss of inherent tannins in the wood.If capital outlay is involved (and it always is) air-drying means that this capital is stagnant for a longer time.

Drying by air, with the wood stacked and stickered to allow free air flow on all six sides, requires real estate. A mill who has both the acreage and can afford to occupy that acreage with stacks of stickered lumber drying at its own leisurely pace.

Purchasing a kiln, either electrical or solar, is expensive, but dramatically improves the turn-a-round of inventory from green tree to retail lumber yard.

But kiln-drying is a risky endeavor and can often result in defects that arise due to what’s called the shrinkage anisotropy, which leads to warping: cupping, bowing, twisting, spring and diamonding. Essentially, the wood tissue is ruptured and the inherent fibers collapse and flatten above the saturation point. In layman’s terms, we are traumatizing the wood fiber, which was often only a few days or weeks before, a living tree in a forest. We are evaporating the life-sustaining moisture content, or ‘greenness’, in an accelerated timetable..

Most air drying is performed as a stipulation by the end user. A regular customer of a specific mill or sawyer, will require the stock be air-dried to better suit his purposes and provide the stability of the wood once acclimated to local conditions. This customer (which by the nature of business almost never involves contractors and carpenters buying direct from their local lumber yard) may also request grain patterns, such as only vertical grain and quarter-sawn grain, to further the assurance of the most dependable stock. This is normally an option only available to those who purchase directly from a mill and in some quantities and with the regularity of a repeating customer. The relationship between a woodworker and his sawyer is paramount to the quality of the end product.

Why bother? Well, why bother putting a period at the end of this sentence It requires almost no ink, and you will likely find the content of the sentence just as readable and legible without the period.

![]()

Wood Talk

4) RENEWABLE HARVEST

The foresight of a sustainable future

We have stalled on this last condition as there is no way to honestly address it without going into a short thesis. A subject more suitable for a book length diatribe that touches on an ensuing medley of not only environmental concerns, but social and cultural as well. So much so that in some ways the subject can only be addressed as a metaphor that skips and dances around the frontal assault of the sort of straight talk the subject deserves. If you are living hand-to-mouth and struggling to meet your monthly needs on a level of bare sustenance, the temptation of more affordable goods at the Wall Mart located in the county seat of most of the heartland states, you can hardly be faulted for eschewing the higher cost of a local Mom and Pop business. Assuming there are any Mom and Pop concerns left, which in Charles’ travels through the blue highways of America, have been decimated and driven to extinction beginning in the late 1970’s, when our original manufacturing state, Massachusetts, went to North Carolina, and the NY apparel industry sent their manufacturing to the sweat shops in Mississippi. A trend that by the early 1980’s had gone overseas, and by the mid 1990’s, with the passing of NAFTA, had all but disappeared from the American landscape. With it, the slow and ineluctable withering of the middle class. Furthered by legislation passed initially by President Clinton allowing a watered-down versions of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act that saw media concerns once restricted to only 30 subsidiaries suddenly allowed 1200! Furthered by President Bush in 2000 to 3,200! The proliferation of corporate bullying was now a sanctioned and acceptable act, drawn from a skewed idea that if the corporations were allowed to grow, their increased profits would show up in larger payrolls for more Americans who had never quite replaced their careers in industry and manufacturing that were lost in the early 1980’s. This was called the Trickle Down Economy, first championed by Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Treasury Secretary, and again by President Hoover. and returned to again by Ronald Reagen. It failed miserably in all three cases, unless you happened to be a corporation, or those who invested in such. In that event, it was wildly successful. To not only the corporations it benefited, but to the voting legislatures who enjoyed a clause that is still in effect today: Congressmen are exempt from the normal insider trading laws governing the common American. In other words, if you as a private citizen receive a secret tip from your neighbor who works for Apple that Apple is about to come out with a new product that will drive up their shares, and you buy Apple stock, you have committed a crime which is punishable by severe prison terms. If you are a congressman who was elected on the funding of a corporation who hires lobbyist to swoon your vote with tips on investment strategy that results in your financial portfolio reaching new heights, you, as a senator or assemblyman, are not breaking the law. The graphs comparing the investments in the stock exchange between congressman and common Americans over the past, shows an imbalance that will convince anyone who has actually read this far into a state of shock.

So what’s all this have to do with our Wood Talk discussion of sustainable, renewable harvest foresting? With building your home improvement using woods that have been planted and grown and harvested in a way that insures there are more forests to harvest in the decades to come? It is simply a long-winded metaphor to explain the short-sightedness, and only true strength of America’s once powerful middle class. It’s cheaper to shop at Home Depot. To buy pressure-treated wood. To see the Home Depot profits funneled to a corporate headquarters nowhere near your home. To ignore the local lumber yard owned by your neighbor who would in turn spend his profits in part at the local shoe store and the local appliance store who would in turn spent their profits by hiring a local carpenter to make improvements to their home, etc etc. This is a local-based economy supporting local interests.

Certifications for renewable harvested wood are simply one of many measures trying vainly and hopelessly to slow this progression and suggest you buy less with the short measure of todays savings and opt for the longer term investment in tomorrow’s return. Driven by your own conscience. Wood certifications are no different than those labeling food sources as organic and local, asking that you opt for an alternative to those large facilities utilizing hormones and additives and pesticides and cruel practices, all of which diminish dramatically the actual nutritional value, but in many cases, most cases, are in fact detrimental to your general health. All of which are sanctioned by the USDA. Not to mention the above concerns regarding the support of local economies. Local businesses over the corporate concerns. Local businesses who are more conscientious of the value of their product if for no other reason, they are selling to their neighbor, whose daughter may very well marry their son that results in a lifetime of holiday gatherings, that results in providing the produce or meat raised on their farm in a manner that will not shorten or denigrate the lives of the newlyweds or, worse, the grandchildren.

A complicated and labyrinthine puzzle that is far far beyond the understanding of the vast majority of American public A class that rarely reads with any critical depth, nor has the mental alacrity to untangle the puzzle without being spoon fed a simplified synopsis comparable to a digestible sound byte. , offered from both sides of the issue. Much much better for them to understand, fully, what is at stake, than to rely on someone else’s explanation. To understand the basic and relevant parameters mentioned here more as a glimpse than an entreaty. To understand wood planted with a conscience will be a better grade of wood that is not harvested too soon, or harvested in what is called Clear-Cutting, annihilating the landscape to a bareness that leads to erosion that leads to toxic waterways and of course, the loss of trees. Trees, and the sheer volume of those in the Amazon (as in Ipe) responsible for so much of the photosynthesis that feeds the atmosphere in a manner that sustains the planet.

A process, by the way, that is reversed when a field of natural grazing grasses are replaced with a grain that is fertilized with pesticides to increase growth and production and provide plentiful feed for grazing cattle. The ensuing crop of grass and grain begins a depletion of the soil’s natural strength, while the run-off in heavy rains fills the creeks and rivers with a soil that is laced with poisons, while providing the grazing cattle with a grain that each year is further demolished of it’s nutritional strength that ends up in hamburgers etc that have only a fraction of the nutrition as does organic, grass-fed beef. Furthered even more by the trend to feed these beef with hormones that improve the productivity and trickle not only into the pot roast served at the wedding of our neighbor’s mentioned above, but into the milk fed to our children, while these same false grains are emitting carbon monoxide into the atmosphere instead of oxygen (the exact opposite of photosynthesis as it was designed several billion years ago).

So, in the vein of this last heading of the four headings associated with exterior joined assemblies, if you were to suddenly buy your wood from a local lumber yard and insist on certification of a sustainable harvest, then that local yard will see to it that it is inventoried when enough requests are made. With each of you who make this decision, that is one less who supports the local big box, and eventually the big box closes and concentrates in those areas where the populace is less educated and less enlightened and chronically poor and if they too begin to whisper their preferences to a local lumber yard, then we will awake one day with the box chains all gone and with that, an American Commerce governed more by local conscience than corporate profits will grow and prosper and all of us, virtually every one of us, will come out winners.

Thank you, and I hope the above material has been informative and helpful and perhaps somewhat enlightening.

![]()